It had been a while since I’d seen Jean-Luc Godard‘s Two or Three Things I Know About Her. Many years ago, before I knew that I wanted to be a fusty old patches-on-elbows-of-tweed-jacket academic (I’m still getting there…), I made a conscious effort to educate myself in the history of cinema. This involved raiding the video collections of Birkenhead Central Library on my way home from work. Their holdings were quite limited, but there was enough to start building up my interest, and I could pick up a few books if I needed a primer on what I was seeing. Lacking a proper education in film studies, I had to seek out film-makers whose reputation was pretty much sealed. It took a while before my own whims and interests could lead me into more obscure corners and develop my own tastes (I’m sure I’m not unusual in that sense). One of the first directors whose ouevre I worked through was Jean-Luc Godard, whose films can be an intimidating starting point. I didn’t catch a lot of the names he dropped, and the sheer volume of work threatened to overwhelm with their radical shifts in tone, style, pace and aesthetic syntax: just when you think you know what to expect from Godard, he decides to try something else instead. On the other hand, he’s an excellent, instructive place to start breaking down preconceptions about what cinema can and should be, since Godard himself is constantly asking himself about the nature of cinema, always monitoring and commenting upon his own process as it develops. And like a good maths student, Godard always shows his working. I offer here my thoughts on the film, sustained by excerpts from some useful writings on the subject from others.

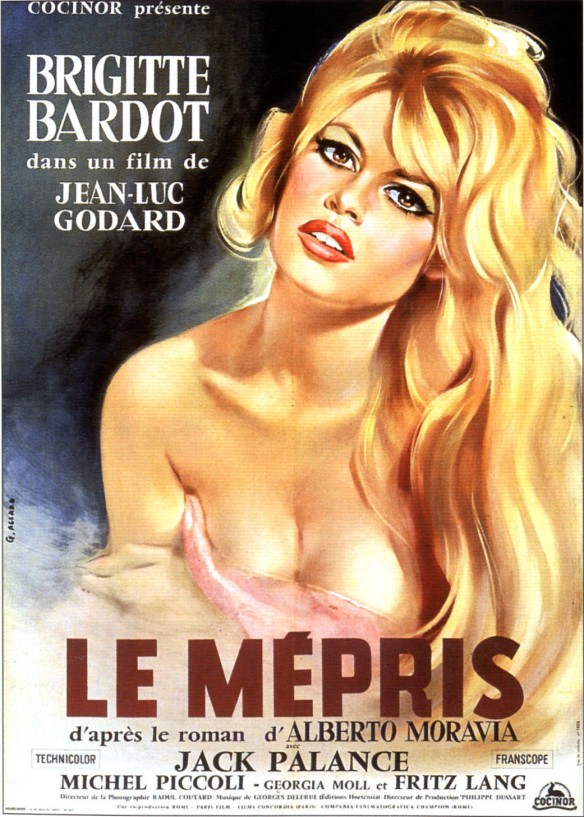

Two or Three Things I Know About Her is one of the trickier ones from Godard’s astonishing run of great films of the 1960s. It’s tricky because it mostly eschews narrative and character exploration (A Bout de Souffle, Vivre sa Vie, Une Femme est une Femme, Bande a Part, Les Carabiniers, Le Mepris and Pierrot le Fou all have much more in the way of linear development and emotive performances, even if they are never conventional in going about it) to focus on politics, language and social stasis. Ostensibly, it follows a housewife-prostitute through her daily routine, interjecting interviews with other women who cross her path, and cutting away to shots of the construction of the Périphérique, a giant ring road that encircled and thus defined what we know think of as central Paris. Katherine Shonfeld explains its significance:

“This road deliberately isolated the sites of working-class occupation in the suburbs in a bid to sanitise the city centre, partly in response to the riots against the Algerian War of the early 1960s. As in previous attempts, the imposition of an excluding line appeared to acerbate the ferment it was intended to suppress. The newly built housing adjacent to the Périphérique, is the setting for Godard’s film.” (p.112)

Douglas Morrey has called it “a film about knowledge, about the necessary uncertainty that inhabits knowledge, about the difficulty of knowing.” (p.61) It incorporates Godard’s abiding interest in prostitution as a metaphor for the cornering of women into positions of exploitation. But if Nana (Anna Karina) in Vivre sa Vie was a tragic heroine struggling to define herself and break out of the cycle of degradation into which she finds herself falling, then Juliette Janson (Marina Vlady) is already resigned to her position, fully subsumed by the system, despite her intellectual resistance through existentialising whenever the opportunity presents itself. As Yosefa Loshitzky has noted:

“A unique aspect of Two or Three Things is its deromanticisation of prostitution (as opposed to Vivre sa Vie, for example). Prostitution is dislocated from its natural environment (the street or the brothel) to the domestic sphere, the reign of the family and domestic sex. Thus, the tension between ordinary (familial) sex and ‘other’ sex (extra-familial, forbidden) is blurred. Juliette, the domestic/suburban prostitute, the new protagonist of consumer society, is fully aware of her submissive function in this society. Yet she does not have the courage (as does Godard’s later feminist heroine, Jane Fonda in Tout va Bien) either to criticise or to rebel against a whole system that encourages prostitution and consumerism.” (p.145)

Shonfeld also notes, in her comparison of the film with Zola’s Nana, that Godard’s heroine “behaves in spite of her own individuality, and directly enacts the social and economic structures which define her.” But the metaphor of prostitution extends beyond women, as Godard explained at the time of the film’s release, in an interview extract reprinted in the handy booklet that accompanies the Nouveaux Pictures Region 2 DVD:

“An article which appeared in thhe Nouvel Observateur relates to a deep-rooted idea of mine. The idea that in order to live in Parisian society today, one is forced, on whatever level, on whatever scale, to commit an act of prostitution in one way or another, or to live according to the rules that govern prostitution.”

Colin McCabe adds that Two or Three… is a film in which “there is no division between legal and illegal money and in which prostitution is no longer opposed to legal ways of earning money … but becomes the exemplary relation to money in our society.” (p.38)

So, Godard argues, we are all forced to prostitute ourselves in order to fit into the structures of society. This idea permeates Godard’s work, whether it is in the form of a film-maker compromising his art, and the respect of his wife, for the sake of a Hollywood paycheque in Le Mepris, or the enactment of a production-line, hierarchical clusterfuck in Sauve qui Peut la Vie (please don’t make me explain that one…). In Two or Three…, this subjection is formalised in several ways. In a scene in a coffee shop, Juliette overhears a conversation about American Imperialism (“they’re American shoes, for stomping on Vietnam and South America”), and immediately orders a Coke. Earlier, she interrupts her husband’s transistor radio session, from which he keeps up with news about the Vietnam war, with a question about stockings as she reads from a fashion magazine. Even as she can step back to observe her situation, expressing her sadness at one point over the fate of the Vietnamese, she is caught up in a world of cues, prompts, routines and conventions. Advertisements and clothes seem to exert a magnetic influence over the women in the film, and Godard gives great prominence to commercial images and logos – while his central characters agonise about communication and alienation, billboards ad magazine spreads are nonchalantly declaiming their wares in big, brutish letters and iconographic statements. Their communicative process is blunt and unambiguous.

The chunky colours of signs and words dropped into the image and the city gain their own graphic power and beauty as Godard makes them into strange bearers of messages and meanings, single entendres imprinted onto the landscape, and aim appears to be to make these images stand out as giant impositions and imperatives, pointing out the artifices of the “common sense” prompts that people so often forget to notice. As David Sterritt puts it:

“Godard accepts such conventions when they rescue the clear, productive reality of objects and images from the artificial signs and manufactures meanings that glut our contemporary world. Common sense becomes his enemy, however, when it lures us into uncritical acceptance of those signs and meanings. The eccentricities and idiosyncrasies of his work are a decades-long howl of protest against cinema that contents itself with reflecting instead of questioning the assumptions of the society around it.” (p.23)

Sterritt also describes Godard’s work in the late-60s and early 70s as a sort of “scorched-earth cinema”, designed to be so formally disruptive of convention that it could counteract the excesses of a consumption-plump Western society. This either results, depending on your perspective, in films that are distancing and uninvolving, or exhilaratingly unpredictable. In Two or Three…, Godard frequently attempts to puncture any immersion in the fiction: he introduces his leading character, Brecht-style, as both actress and character, and the direct-to-camera interviews are asides to the spectator that disrupt any accumulation of story to focus on everyday people. All of his interview subjects, apparently fed questions through an earpiece and improvising their responses, are attractive, stylish young women, suggesting that Godard is not particularly interested in a cross-sectioned, universal picture of a city under the thumb of consumerism, but instead sees women as singularly victimised.

His interviewees often look uncomfortable, eyes darting from side-to-side as if unsure whether or not they should make eye contact with the camera or stay “in character” as components of the diegesis. Godard doesn’t see this as a problem; he’s not hierarchising reality effects or seamless interweavings of fragments in his collage of images. These are moments where a sense of truthfulness flashes into view even as the posing makes it seem a little staged. Godard expresses anxiety about his own process of communication in his ongoing “director’s commentary”, a whispered voiceover that fusses over the most appropriate way to show something. Rather than imposing an auteur’s authoritative delivery onto the film (“it’s correct because I’m a genius”), he incorporates the process of shot selection into the film’s assemblage of scenes, techniques and styles. Again, I like Douglas Morrey’s description of this process:

“Thought emerges not as an ordered sequence, but as a chaotic jumble; it seems impossible to fix attention on one thought without another interrupting it. And this sense of chaos and interference constantly greets the spectator seeking knowledge through Godard’s film. Rather than present us with images, sounds and ideas that can be immediately recognised and assimilated to our pre-exisiting categories of understanding, Godard forces us to confront the difficulty of making sense of the world, the violence which accompanies the process of learning. Often Godard will cut into an image or a sound that is not instantly recognisable and presents us with a pure, unassimilable difference. Such is the case with the sudden, intensely loud bursts of construction noise, or the extreme close-up on the paintwork of Juliette’s red Mini as the light plays over it: this is not an image of a car, but of the pure difference of colour and light. […] Godard refuses an approach based in separation and negation, refuses to distinguish between that which is and is not suitable material for a film.” (p.68)

Colin McCabe also describes this very effectively:

“The importance of the film is that it abandons all attempts to give classical narrative determination to its protagonist, Juliette Janson (Marina Vlady), who engages in … part-time prostitution. Instead of an attempt to place her in narrative, Godard’s own voice on the sound-track poses the question of her position. But the sound-track has none of the dominance over the image that is associated with classic documentary. The opening shots of the film, which present Juliette Janson, make this clear. Whether regarded as fictional or real, Godard cannot identify the colour of her hair and he misdescribes her actions. Insofar as Juliette’s position in the film is determined, it is determined by the advertisements that constantly produce images for her. It is the relation between image and spectator, the articulation of the production and distribution of images, that are the focus of the film’s investigation and this entails the position of the spectator of the image, be it Godard or the cinemagoer, being immediately posed in the film itself.” (p.39)

Godard’s apparent anxiety about the inadequacies of language and the ambiguity of images leads to the problem of how best to shoot something, the documentarian’s quandary of how remove one’s partiality from the image and leave it untainted by idiosyncrasy. But I’m sure Godard was aware that, by holding that debate, by voicing that anxiety in full view of the spectators, he was making an idiosyncratic, personal film that editorialises and tells us a great deal about communication, and about the difficulty not just of expressing oneself but of being heard at all above the din when you live in a tenement block at the edge of a road built to cut you off from much of the city.

References:

- Yosefa Loshitsky, The Radical Faces of Godard and Bertolucci. Wayne State UP, 1995.

- Colin McCabe, Godard: Images, Sounds, Politics. BFI, 1980.

- Douglas Morrey, Jean-Luc Godard. Manchester UP.

- Katherine Shonfeld, Walls Have Feelings: Architecture, Film and the City. Routledge, 2000.

- David Sterritt, The Films of Jean-Luc Godard. Cambridge UP, 1999.

[BLOG IN PROGRESS. I started this post hoping it might be of benefit to my students. As much as I love the film, I know it can be off-putting to non-film specialists, and to plenty of other people unfamiliar with Jean-Luc Godard‘s style of filmmaking. I intend it to be an ongoing post, and will add to it periodically, so if you have any thoughts about the film, or anything you think that viewers need to know about Le Mépris in order to get maximum interest from it, leave a comment below with your ideas and suggestions. In particular, I’d like to hear from anyone who found this post useful in getting to grips with the movie: what did you find most helpful or informative?]

[BLOG IN PROGRESS. I started this post hoping it might be of benefit to my students. As much as I love the film, I know it can be off-putting to non-film specialists, and to plenty of other people unfamiliar with Jean-Luc Godard‘s style of filmmaking. I intend it to be an ongoing post, and will add to it periodically, so if you have any thoughts about the film, or anything you think that viewers need to know about Le Mépris in order to get maximum interest from it, leave a comment below with your ideas and suggestions. In particular, I’d like to hear from anyone who found this post useful in getting to grips with the movie: what did you find most helpful or informative?]

![Eyes Wide Shut Censored version [Click to Uncensor] Eyes Wide Shut Censored version [Click to Uncensor]](https://drnorth.files.wordpress.com/2009/11/eyes-wide-shut-censored-version.jpg?w=584)

A slideshow of images from Cecil B. DeMille’s 1932 epic of persecuted Christians in ancient Rome. I’ve been testing out the compatibility of the various pieces of my online “presence”, e.g.

A slideshow of images from Cecil B. DeMille’s 1932 epic of persecuted Christians in ancient Rome. I’ve been testing out the compatibility of the various pieces of my online “presence”, e.g.  [This post refers to the first two Johnny Weissmuller Tarzan films,

[This post refers to the first two Johnny Weissmuller Tarzan films,