[BLOG IN PROGRESS. I started this post hoping it might be of benefit to my students. As much as I love the film, I know it can be off-putting to non-film specialists, and to plenty of other people unfamiliar with Jean-Luc Godard‘s style of filmmaking. I intend it to be an ongoing post, and will add to it periodically, so if you have any thoughts about the film, or anything you think that viewers need to know about Le Mépris in order to get maximum interest from it, leave a comment below with your ideas and suggestions. In particular, I’d like to hear from anyone who found this post useful in getting to grips with the movie: what did you find most helpful or informative?]

[BLOG IN PROGRESS. I started this post hoping it might be of benefit to my students. As much as I love the film, I know it can be off-putting to non-film specialists, and to plenty of other people unfamiliar with Jean-Luc Godard‘s style of filmmaking. I intend it to be an ongoing post, and will add to it periodically, so if you have any thoughts about the film, or anything you think that viewers need to know about Le Mépris in order to get maximum interest from it, leave a comment below with your ideas and suggestions. In particular, I’d like to hear from anyone who found this post useful in getting to grips with the movie: what did you find most helpful or informative?]

In summary, it’s part domestic drama, in which a man tries to find out why his wife no longer loves him, and part meta-cinematic backstage dramatisation of the adaptation process, in which that man struggles with his job as a screenwriter on an American film of Homer‘s Odyssey. Filmed as the Hollywood studio system collapsed, Le Mépris is a meditation on the relationship between art and life, film and reality.

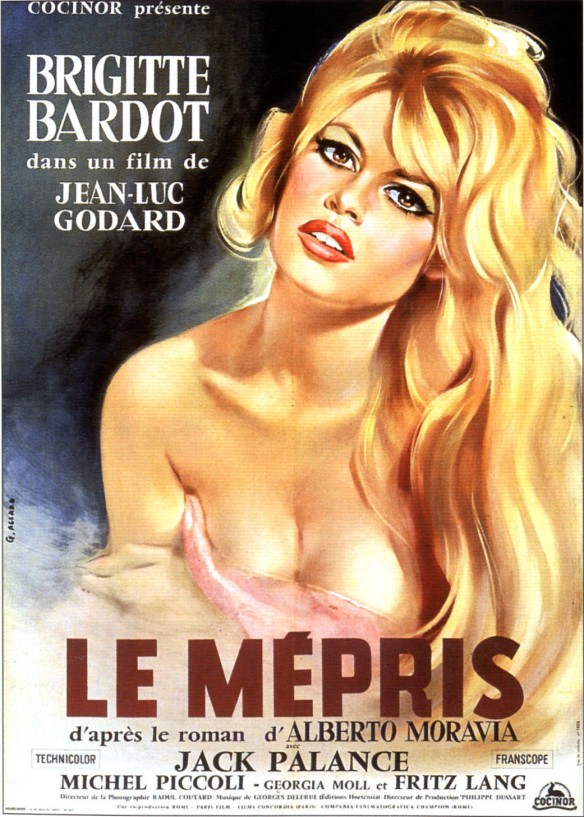

The plot, such as it is, focuses on Paul Javal (Michel Piccoli), a screenwriter who is approached by American film producer Jeremiah Prokosch to rewrite the script of a new adaptation of Homer’s Odyssey. The current director, Fritz Lang, has not been living up to Prokosch’s expectations, and he wants a new script to focus on the psychology of Ulysses and his relationship with his wife, Penelope. Meanwhile, Paul’s relationship with his wife, Camille (Brigitte Bardot) has deteriorated for reasons he cannot explain. As he tries to fathom the mysteries of her sudden contempt for him, he finds himself caught in the middle of a struggle between Lang (art) and Prokosch (commerce) as he has to decide whether to take the Hollywood dollar and compromise his art in the hope that he might hold on to his wife. But is his attitude to the cinema connected to his wife’s feelings for him?

The plot, such as it is, focuses on Paul Javal (Michel Piccoli), a screenwriter who is approached by American film producer Jeremiah Prokosch to rewrite the script of a new adaptation of Homer’s Odyssey. The current director, Fritz Lang, has not been living up to Prokosch’s expectations, and he wants a new script to focus on the psychology of Ulysses and his relationship with his wife, Penelope. Meanwhile, Paul’s relationship with his wife, Camille (Brigitte Bardot) has deteriorated for reasons he cannot explain. As he tries to fathom the mysteries of her sudden contempt for him, he finds himself caught in the middle of a struggle between Lang (art) and Prokosch (commerce) as he has to decide whether to take the Hollywood dollar and compromise his art in the hope that he might hold on to his wife. But is his attitude to the cinema connected to his wife’s feelings for him?

Jean-Luc Godard, the director of Le Mépris, was a high-profile figure in French cinema, on the strength of his association with the Nouvelle Vague, and in particular his hugely successful and deeply cool À bout de souffle. However, two of his previous films produced by Carlo Ponti and Georges de Beauregard, Une Femme est une Femme (1961, a deconstructed musical starring his wife, Anna Karina) and Les Carabiniers (1962) were rejected by audiences. Godard and Brigitte Bardot had both expressed a desire to work together. Still hoping to work with Ponti, who was a very powerful producer, Godard offered to make a “classical” film, something more accessible to popular audiences than the earlier films, based on a novel of Ponti’s choice. If the job of a “classical” studio director was to serve the narrative without personalising the material with an excess of stylistic ostentation, Godard’s approach is different. His films are often a collage of stylistic experiments, quotations, and self-conscious techniques that foreground their form. That is to say, he doesn’t just serve a story or present you with realistic depictions of characters in a fictional setting; his films are stuffed with ideas, and new ways to shoot even a simple dialogue scene might be invented on the spot. Depending on your point of view, this can give his early works in particular either a scrappy, “anything goes” feel that seems somewhat amateurish, or that same approach makes the films feel urgent, exciting, and alive with the possibilities offered by the medium. Godard’s work developed beyond the louche, freewheeling early days of the French New Wave, becoming increasingly political, often didactic, and more and more challenging. But the strain of melancholy, and the reflective, mournful evocation of film history that reached something of a heightened pitch in Le Mépris is a constant in his oeuvre.

The Adaptation of Alberto Moravia’s novel provides a thematic and narrative spine to Godard’s film, and some scenes follow it quite closely (the central dialogue sequence in Paul and Camille’s apartment compresses the book’s relationship issues and follows a similar order of the marriage’s dissolution), but Godard departs from the source material considerably. Moravia’s book is a rather urgent, agonised internal monologue by a man desperate to find out why his wife hates him, smarting from the slights to his masculinity and his integrity. HIs wife initially denies the accusations that she hates him, but ultimately admits it under his constant questioning (for a while, a reader might suspect that he is imagining it, projecting his own anxieties onto his wife). But she won’t give him a reason. The central idea seems to be the impossibility of truly knowing someone else’s mind, or the danger of defining one’s sense of self by another person’s validation. It could just as easily, however, be a ‘realistic’ vision of how relationships break down under misunderstood or mismatched desires. The book also contains the theme of filmmaking. The narrator is, as in Godard’s film, a screenwriter hired to rewrite scenes for an adaptation of The Odyssey. It is Godard’s decision to make it about a Hollywood production in Italy, rather than an Italian film. Moravia also has a German director at the heart of his story, but his Rheingold is something of a blustering buffoon, absorbed by cinema and unable to speak of anything else (a stark contrast to Godard’s humane and warm depiction of Fritz Lang). The crucial difference is that in the book, it is the Italian producer who wants to make a classical adaptation of Homer’s epic poem, and the German director who wants to create a psychologically realistic portrait of an epic Hero. Godard reverses this antagonism, so that Fritz Lang is the classicist, and Prokosch, the American producer, the one who wishes to psychologise the marriage of Odysseus and Penelope.

Language is a recurring theme in the movie. There is dialogue in French, English, Italian, German, and it’s about the translation of an ancient Greek epic poem into the language of cinema, in Italy. Godard even took his name off the Italian release of the film, because all the speaking parts had been dubbed into Italian, erasing the communication problems that provided such a strong throughline for the film. It’s not that the plot is driven by the various characters failing to understand one another, but rather that the fact that they often need have their comments translated drives a wedge between the speakers: there’s a gap between speech and response, and always the potential for misunderstanding. One problem between Paul and Camille (who both speak in French throughout) may be that language is inadequate to the task of understanding one another. The centrepiece of the film is a 30-minute dialogue scene in which we watch the couple’s relationship oscillate between affection, passive-aggression, hatred, rage, violence, acceptance and everything in between. Godard allows words to carry a heavy burden in this scene – even though he keeps up a variety of shot selections, camera movements and even costume changes so that it isn’t too static, the focus is on how they argue, and how their words fail to fully express why he suspects her, and why she resists, and ultimately despises him.

- There is a quotation in the opening title sequence: “The cinema substitutes for our gaze a world more in harmony with our desire. This is the story of that world”. Does Godard want this opening statement to guide our interpretation of the film? Is the world depicted in Le Mépris in harmony with our desires, or is it a film about people seeking to create a cinema that matches their desires? In any event, the quotation is attributed to the great French critic Andre Bazin, a founder of Cahiers du Cinema and father figure to the Nouvelle Vague, but it was actually said by Michel Mourlet in Cahiers essay of 1959. Jonathan Rosenbaum was sharp enough to pick that one up.

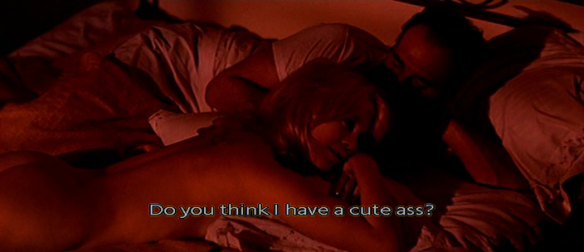

Brigitte Bardot was a huge star in the early 1960s. The film plays with her star image, which had been largely built around her incendiary sex appeal in films such as And God Created Woman… (1956), and the extraordinary amount of press interest she generated. At the time of Le Mépris, she had taken a break from acting to try and escape from the media’s attention, so this film was a highly anticipated return to the screen. While it’s certainly true that Godard exploits her looks, lingering on her pouting lips and alarming curves, and finding multiple opportunities for her to bathe or lie around unclothed, he draws out a theme of sexual objectification in the process. This is no more blatant than in Bardot’s first appearance. She lies nude on a bed, canoodling with her onscreen husband Michel Piccoli, in a possibly post-coital sequence of tender conversation that precedes the disintegration of their marriage: the scene is the only solid marker of a pre-contempt marital bliss. Bardot asks her husband his opinion about various parts of her figure, verbalising the fetishistic, cataloguing of body parts that the camera performs as it glides, in an unbroken take, up then down her back. This scene was inserted when Joseph E. Levine insisted on a certain number of Bardot nude scenes. Godard’s response is a scene that resists easy eroticisation: instead of allowing the viewer unalloyed voyeuristic pleasure, Bardot’s commentary on her own attributes reminds us that she knows she’s being looked over, and that our inspecting gaze is not innocent, invisible or unnoticed. This sequence is a good example of Godard allowing form to speak over, or through the content: The colour filter on the shot begins red, changes to white, then turns blue. There is nothing in the scene to suggest that it needs a tricolour imposed upon it, and the lights are not changing in Paul and Camille’s bedroom; the formal stamp that Godard adds to the shot (i.e. the look he gives it through his selection of a particular technique) is added on as surplus to the image rather than serving only the communication of narrative information or realistic detail about the room in which the scene takes place. This sequence also interrupts the shot which precedes it. The opening title sequence has a voiceover reading out the cast and credits while a long take shows us Raoul Coutard’s camera on rails tracking Francesca Vanini / Giorgia Moll on her way to the Cinecitta studios. Then we have the insert of Paul and Camille in bed together, before abruptly cutting back to Paul and Francesca meeting on the street.

Brigitte Bardot was a huge star in the early 1960s. The film plays with her star image, which had been largely built around her incendiary sex appeal in films such as And God Created Woman… (1956), and the extraordinary amount of press interest she generated. At the time of Le Mépris, she had taken a break from acting to try and escape from the media’s attention, so this film was a highly anticipated return to the screen. While it’s certainly true that Godard exploits her looks, lingering on her pouting lips and alarming curves, and finding multiple opportunities for her to bathe or lie around unclothed, he draws out a theme of sexual objectification in the process. This is no more blatant than in Bardot’s first appearance. She lies nude on a bed, canoodling with her onscreen husband Michel Piccoli, in a possibly post-coital sequence of tender conversation that precedes the disintegration of their marriage: the scene is the only solid marker of a pre-contempt marital bliss. Bardot asks her husband his opinion about various parts of her figure, verbalising the fetishistic, cataloguing of body parts that the camera performs as it glides, in an unbroken take, up then down her back. This scene was inserted when Joseph E. Levine insisted on a certain number of Bardot nude scenes. Godard’s response is a scene that resists easy eroticisation: instead of allowing the viewer unalloyed voyeuristic pleasure, Bardot’s commentary on her own attributes reminds us that she knows she’s being looked over, and that our inspecting gaze is not innocent, invisible or unnoticed. This sequence is a good example of Godard allowing form to speak over, or through the content: The colour filter on the shot begins red, changes to white, then turns blue. There is nothing in the scene to suggest that it needs a tricolour imposed upon it, and the lights are not changing in Paul and Camille’s bedroom; the formal stamp that Godard adds to the shot (i.e. the look he gives it through his selection of a particular technique) is added on as surplus to the image rather than serving only the communication of narrative information or realistic detail about the room in which the scene takes place. This sequence also interrupts the shot which precedes it. The opening title sequence has a voiceover reading out the cast and credits while a long take shows us Raoul Coutard’s camera on rails tracking Francesca Vanini / Giorgia Moll on her way to the Cinecitta studios. Then we have the insert of Paul and Camille in bed together, before abruptly cutting back to Paul and Francesca meeting on the street.

The temporal disruption matches the interruption caused to the filming by Levine’s insistence on added nudity. The scene bears the scars of its offscreen clash of interests, because Godard refuses to incorporate it smoothly into the film, but instead lands it right in the middle of a shot and its reverse shot.

Fritz Lang was a German film director best known for the epic scale of his films Die Niebelungen (1924; based on an epic poem c.1200AD), the science fiction milestone Metropolis (1927), and his series of films about the fictional criminal mastermind Dr Mabuse (1922/1933/1960). Lang wrote, so he says, a lot of his own lines for Le Mépris, or at least he retells some of his favourite aphorisms (“Cinemascope isn’t for human beings, it’s for snakes and funerals”) and industry anecdotes. He embodies both European epic filmmaking and classical Hollywood: after fleeing the Nazi regime in 1933, he made his way via France to the USA, where he directed more than two dozen movies. By the time of Le Mépris, his sight was failing and he had already made his final feature. His visible frailty, belied by his combative spirit and lively mind, add to the sense of the passing of the Hollywood studio system. There’s a hint in the film that Camille’s hatred of Paul might stem from his treatment of Lang, as shown in his initial willingness to rewrite the Odyssey screenplay at the behest of Prokosch and his cheque-book. The anecdote about Lang refusing Goebbels‘ offer to make Nazi propaganda films, choosing principal over lucre, stands in stark (if disproportionate) contrast to Paul’s failure to resist the lure.

Fritz Lang was a German film director best known for the epic scale of his films Die Niebelungen (1924; based on an epic poem c.1200AD), the science fiction milestone Metropolis (1927), and his series of films about the fictional criminal mastermind Dr Mabuse (1922/1933/1960). Lang wrote, so he says, a lot of his own lines for Le Mépris, or at least he retells some of his favourite aphorisms (“Cinemascope isn’t for human beings, it’s for snakes and funerals”) and industry anecdotes. He embodies both European epic filmmaking and classical Hollywood: after fleeing the Nazi regime in 1933, he made his way via France to the USA, where he directed more than two dozen movies. By the time of Le Mépris, his sight was failing and he had already made his final feature. His visible frailty, belied by his combative spirit and lively mind, add to the sense of the passing of the Hollywood studio system. There’s a hint in the film that Camille’s hatred of Paul might stem from his treatment of Lang, as shown in his initial willingness to rewrite the Odyssey screenplay at the behest of Prokosch and his cheque-book. The anecdote about Lang refusing Goebbels‘ offer to make Nazi propaganda films, choosing principal over lucre, stands in stark (if disproportionate) contrast to Paul’s failure to resist the lure. Jack Palance plays the producer of a new film of Homer’s Odyssey. Palance (1919 – 2006) was a tall, handsome leading man, with rather menacing features (those cheek-bones!). The received wisdom is that Godard based Prokosch on the film’s American producer, Joseph E. Levine (1905 – 1987), who was noted for his “sword-and-sandal” or peplum movies that made commercial movies out of classical myths and heroic legends. This was Godard’s first and only job for an American producer, and it disillusioned him of many of his romantic notions about the Hollywood studio system. But to assume that Godard was simply “against” his American producer is too obvious. Certainly, Jack Palance is made to seem a little ridiculous, striking heroic poses, quoting cod-philosophical aphorisms from his tiny red book, chuckling with uncontrollable glee at the sight of naked girls onscreen, and even paraphrasing the (famously misattributed) Joseph Goebbels line “whenever I hear the word ‘culture’ I reach for my gun”. Sometimes Godard shoots him from a low angle, to play up his mock-heroic stature:

Jack Palance plays the producer of a new film of Homer’s Odyssey. Palance (1919 – 2006) was a tall, handsome leading man, with rather menacing features (those cheek-bones!). The received wisdom is that Godard based Prokosch on the film’s American producer, Joseph E. Levine (1905 – 1987), who was noted for his “sword-and-sandal” or peplum movies that made commercial movies out of classical myths and heroic legends. This was Godard’s first and only job for an American producer, and it disillusioned him of many of his romantic notions about the Hollywood studio system. But to assume that Godard was simply “against” his American producer is too obvious. Certainly, Jack Palance is made to seem a little ridiculous, striking heroic poses, quoting cod-philosophical aphorisms from his tiny red book, chuckling with uncontrollable glee at the sight of naked girls onscreen, and even paraphrasing the (famously misattributed) Joseph Goebbels line “whenever I hear the word ‘culture’ I reach for my gun”. Sometimes Godard shoots him from a low angle, to play up his mock-heroic stature: But Godard has a much more ambivalent and complex relationship with commercial cinema, and Hollywood in particular, than such characterisations would suggest. As Walter Stabb reminds us,

But Godard has a much more ambivalent and complex relationship with commercial cinema, and Hollywood in particular, than such characterisations would suggest. As Walter Stabb reminds us,

the simplicity of relying on the paradigm; art/ commerce, good/bad, director/producer denies both the collaborative complexity of cinema production and Godard’s intelligence as a director who uses the character Prokosch not just to ridicule the role of the producer but to contrast and examine the failings of the ‘artists’ on set.

The depiction of Prokosch, then, is not just a backstabbing hatchet job to show the vulgarity of Hollywood, but a catalytic converter for other characterisations. Godard’s relationship with Palance was not, by all accounts, an easy one, but this fed into the dynamics of the production:

Godard draws both a seething frustration and a bristling restraint out of Palance. Brought to life in Prokosch are the confidence and presence of Palance the star, tempered by an underlying discomfort, best exemplified by the flow of languages on both set and screen that leave Palance alienated.

The stars, Palance and Bardot, whatever Godard does with them, embody that overlap between art and commerce: they ensure the interest of financiers and audiences, and bring a lot of intertextual baggage with them, but they offer Godard much of the freedom that comes with funding, and the power to play with those pre-existing star images. Of course, there are trade-offs: the commercial potential of larger-budget films leads to greater interference from risk-averse producers, as suggested by Levine’s nudie reshoots (see the Brigitte Bardot section above, and the Godard interview below), but Godard is alive to the challenges of this, and the film is enriched by the endlessly tangled web of interplays between art and industry that make up its plot as well as its backstage intrigues. A few years after the shooting, Godard was asked about his relationship with Palance:

There was no relationship. I don’t know if you remember the shot where he throws reels of film in the projection room? Well, he was throwing them at me. I just kept the camera rolling. He was very angry doing the movie. Maybe it was because we were very rough to everyone but Brigitte Bardot and he was a little shocked by that. It was my fault and he became angry. Two or three months later I saw him in Paris and I think he was glad he had made the film.

More Stuff

For your viewing pleasure, here are some useful videos about the film. First, Godard is interviewed by Francois Chalais for Cinepanorama in 1964. In this particularly lucid, direct discussion, he talks about critics, bad reviews and Bardot’s nudity in Le Mépris: Godard responds to Chalois’s repetitive, slightly salacious questions about Bardot with patience and a minimum of fuss:

Godard makes it sound as though the nudity not a major point of contention, but cinematographer Raoul Coutard has claimed that producer Joseph E. Levine furiously demanded reshoots because the first cut of the movie didn’t have shots of Bardot’s bottom.

The film’s trailer is justifiably famous. It foregrounds Georges Delerue‘s magnificent score, and basically consists of Bardot and Piccoli listing all the stuff that’s in the film. It shows off the beauty of the film’s imagery, even as it reduces it all to a set of components manoeuvred into position for your entertainment:

Here’s a one-hour documentary built around a conversation between Godard and Lang under the title Le dinosaure et le bébé:

If you speak French, you can appreciate this slightly creepy documentary (split into two parts on YouTube) about the paparazzi stalking Bardot during the filming on Capri. An unsettling (and hardly surprising) look at the prurient interference of the paps that must have been a nuisance around the set:

The excellent video interview archive Web of Stories has a series of extracts from an interview with cinematographer Raoul Coutard, where he talks about the filming of Le Mepris and working with Godard. Just follow this link.

On Twitter, Emma Green (@emmafgreen) tweeted me this great pic of Piccoli and Bardot during shooting of a scene in a car (it comes just after their long dialogue sequence in their apartment, on their way to meet Prokosch and Lang at the cinema):

If you want to read more, try Terry S. Kim’s article about Godard’s women, which includes extended discussion of Bardot’s role in this film; or maybe Roberto Donati’s analysis of the film’s mise-en-scene.

What an incredibly detailed and interesting piece! I’m normally averse to such an analytical, slightly academic approach, but you definitely make that work. The video about the paps stalking Bardot is fascinating too. That’s a problem that’s been with us a long time. Good stuff. I’ll be back for more.

Pingback: Contempt (Le Mepris)- Jean-Luc Godard | SP Film Journal

I am not a student but a fan. Whwen I turn friends on to Le Mepris I mame sure their first stop is this blog. I am on my way to searching to see if Dr. North has an entry on thebnew Godard film, Adieu a langag. Great discussion of Contempt. May be the most expansice, articulate, and thorough discussions of a great film in a concise write up I have ever seen

Pingback: Le Mépris: Godard, marriage and movie-making | Girls Do Film