You can download a PDF version of this post here. In the PDF version, the layout and images are a little more carefully formatted and stable.

[This post is intended for readers who’ve already seen Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now: it contains major spoilers, and assumes knowledge of the plot. If you need a reminder of the story, try here. I wrote most of this while re-watching the film (trying to practice typing without looking at the keys!), so apologies if some of the prose is a bit scrappy. I’ve polished up some of it, but thought I’d leave most of it intact.]

Don’t Look Now is, when taken from one particular angle, a film about imperfect vision. It shows us a story of eyes deceived, beliefs challenged by visual evidence, even as the film itself conducts its own experiments in superhuman looking by conjoining separate spaces through graphic matches that suggest a world ordered not by random chance but by the interconnectedness of disparate phenomena. The tension between these two kinds of vision, the one flawed, partial and human, the other selective and authoritative, is one of the things that makes the film work and helps to structure its ambiguous play with superstition and clairvoyance.

It might seem like a film about mystery, but it’s all signposted from the first scene, where the kids play outside while the parents read and talk indoors. Various cinematic techniques are used to introduce the question of vision, and to make affective links between characters who might not otherwise be spatially connected. Above, you can see a pair of consecutive shots in which Laura (Julie Christie) puts her hand to her mouth, followed immediately by a cut to her daughter doing the same. In another example, little Christine throws a ball, and the next shot shows her mother catching a packet of cigarettes:

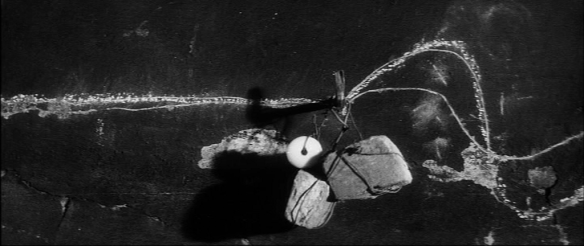

Matches-on-action are usually used to imply spatio-temporal continuity between separate shots of the same activity , but here the matches are between distinct locations. These seem like superficial matches to show the prelapsarian unity of the family, but the graphic matches are used at several points in the film to draw connections between various phenomena. The visual similarity of the red forms of spillage on the photograph and the drowned child’s coat (the red zones occupy roughly the same areas of the frame) sets up a portentous link between the two moments, a clue which John (Donald Sutherland) will spend the rest of the film refusing to acknowledge:

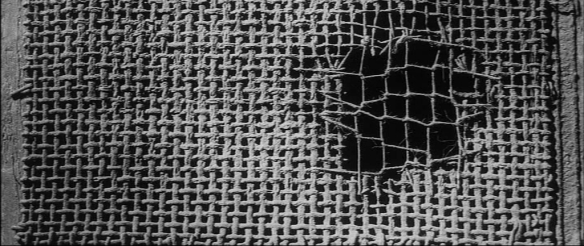

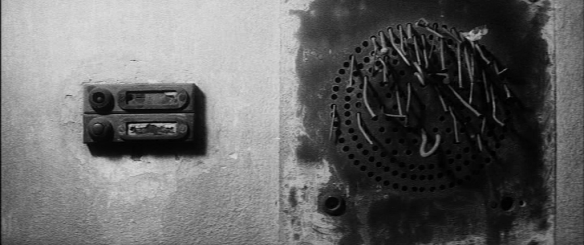

But if the connection between the church and Venice and the death of the child is meant to serve as a warning, then why is it built on similarity? The dwarf and the child are not the same, and it is a confusion between the two which will ultimately lead John into mortal danger. If the supernatural world is sending messages, then they are not clearly legible ones. Elsewhere, vision is portrayed as untrustworthy, partial and fragmented, with faces obscured or ambiguous figures glimpsed:

Julie Christie meets the two English women when one of them gets something in her eye (the other is blind): mirrored images in the bathroom fragment vision. This film is fascinated by the tricks eyes can play, or the beauty of certain effects: light playing on the canal connects to the rain falling on the pond, igniting a memory of the aftermath of Christine’s death. Through the figure of a blind psychic, the film entertains the possibility of a superior mode of sight that comes from sense experiences beyond the eyes.

Does the film want us to conclude that the woman really is psychic and having visions of death and the dead, and thus that it is Sutherland’s incomplete vision, his disbelief in the fact that his daughter is not there in Venice with them that leads him to be killed? Or does it let the viewers decide for themselves whether the premonitions are real? Actually, I suspect it makes it fairly clear that faith in biological sight is misplaced.

The pile-up of blurred lines between memory, premonition and present experience is the organising principle of the justly famous sex scene. Notable amongst movie sex for being a regenerative moment between a married couple as opposed to an inevitable plotpoint for a male hero and his designated shag, it also fits perfectly with the film’s visionary aesthetic. Beginning with tender foreplay, as the lovemaking escalates, it is intercut with flashforwards to shots of the couple dressing and remembering the sex. As the forward-looking shots become more frequent, they might be seen to take over, making the present action into flashbacks, or at least overlapping the temporal spaces and endowing each image with multiple indentities as present moments, memories or predictions and working them into an affective whole of conflated experiences. Perhaps this scene suggests a moment of closeness between the couple by allowing them a privileged, unified experience where the moment, its aniticipation and its memory all come together: it’s a shame that subsequently, they will judge these multi-temporal visions very differently.

If you’ve ever been to Venice and walked around without a map, you’ll know how perfectly cast it is as the backdrop for this story. Any stroll through the backstreets, particularly at night, can turn into a fiendish, circular journey where landmarks will seem to repeat in random order, canals will seem to move their position or reverse their direction. It’s eerie how easily Venetian pathways can mess with your sense of direction, your faith in your remembrances of space, place and time. Out of the holiday season, it’s a mournful, even morbid place, and the film exploits these qualities to the full by making it an architectural analogue of the characters’ mental and visual indecisions. The blind psychic, on the other hand, can navigate it with ease because the sounds are so acute, the echoes so instructive. It is vision, often the most trusted of the senses, that is portrayed as unreliable.

It’s a film about grief, but grieving doesn’t mean sitting around crying – for this couple it means considering and modifying their beliefs about death, time and memory. Laura hides her medication, favouring the clarity of natural vision over medically regulated perspective. John sees his wife’s supernatural beliefs as irrational; he describes her to the authorities as “not a well woman”, and it is this refusal to attribute visual evidence to something other than physical presence that leads him into danger: seeing something that looks like his daughter, he cannot connect the little figure in the red coat whose appearance has been previsualised and warned against. Ultimately, then, the film is reliant on John’s misperception, building up to a shock ending that is foreshadowed heavily in the opening scene and in every other glimpse of his killer-to-be.

The collage of momentous fragments of the opening scene is matched by the death-throes montage that unlocks its significances at the end: all the pieces of the puzzle find their connections to one another in a final spatio-temporal flurry of overlapping times and places, signs and omens. The visual trope of the graphic match, where dwarf and child are made to appear similar, coded by the vivid red macs they wear, even repeating the shot of each figure reflected in the surface of the water, tricks John into accepting that his daughter might be alive before his eyes. But these cannot be John’s vision, because he wasn’t there to see Christine reflected in the water – the film is repeating its own imagery, and giving equal significance to this kind of visual inference and to witnessed sightings, ensuring that seeing something firsthand is not given precedence over other kinds of knowledge and belief. John and has wife have shared similar experiences and interpreted them in very different ways. He sees a premonition of his own funeral but can’t believe that it isn’t evidence of Laura’s physical presence, and can’t accept that his senses might have deceived him. She blithely accepts the evidence of second sight, while he ignores all of the portents, and is punished for trying to believe his senses in the face of other forms of evidence.

You can download a PDF version of this post here. In the PDF version, the layout and images are a little more carefully formatted and stable.

Links:

[I’ve been adding to this post occasionally since I first published it on 8th October 2008. I tagged it as a work in progress, but now that I’ve commented a little on every shot, I thought I’d publish the updates (it has more than doubled in length since it first appeared) and declare it (almost) finished. I will continue to update it every once in a while, but I hope you find it interesting and informative in its present form. I still invite comments or further information from anyone who’d like to add to the essay, or who has links or bibliographic references to recommend.]

[I’ve been adding to this post occasionally since I first published it on 8th October 2008. I tagged it as a work in progress, but now that I’ve commented a little on every shot, I thought I’d publish the updates (it has more than doubled in length since it first appeared) and declare it (almost) finished. I will continue to update it every once in a while, but I hope you find it interesting and informative in its present form. I still invite comments or further information from anyone who’d like to add to the essay, or who has links or bibliographic references to recommend.] [This post refers to the first two Johnny Weissmuller Tarzan films,

[This post refers to the first two Johnny Weissmuller Tarzan films,

See also:

See also: 15 minutes in, we’re at the court of Jabba the Hutt, a giant slug-thing as capriciously sultanic as a Charles Laughton performance. This is a shot that has been added for the Special Edition re-release of 1997. The two humanoid girls are dancers from the house band (their parts were added when George Lucas decided to expand the group’s musical number to a full-blown muppet-fest),

15 minutes in, we’re at the court of Jabba the Hutt, a giant slug-thing as capriciously sultanic as a Charles Laughton performance. This is a shot that has been added for the Special Edition re-release of 1997. The two humanoid girls are dancers from the house band (their parts were added when George Lucas decided to expand the group’s musical number to a full-blown muppet-fest),  A little later, at the film’s halfway point, we have an exhilarating chase on the literally named speeder bikes through the forests of Endor. It’s all forests on Endor. The motion blur on the scenery, accentuated by the sharp focus on the biker scout (used to be one of the favourites in my

A little later, at the film’s halfway point, we have an exhilarating chase on the literally named speeder bikes through the forests of Endor. It’s all forests on Endor. The motion blur on the scenery, accentuated by the sharp focus on the biker scout (used to be one of the favourites in my  An an unenlightened child, it always puzzled me why these mighty, wise warriors, good or evil, didn’t just kill each other. Instead they brandish statements like “give into your hatred” or “if you strike me down I shall become more powerful than you can possibly imagine”. Really? Do they want to be killed or not? What happened to the old ways of goodies and baddies trying to kill each other because each represented a threat to the other’s plans? And why did Darth Vader kill Obi-Wan Kenobi if he knew it would make him more powerful? Only later did I understand that the plan was to turn Luke Skywalker into an asset of evil and turn him to the Dark Side. This might seem like a spiritual conception of evil as a corrupting infection that requires a single transgressive act (tellingly centred around the killing of a feared enemy) to let the infection take over the body and mind, but it’s also a conservative one where you either are or are not wicked and get branded as such. In any case, by the end we still wind up with the Emperor preparing to kill Luke once and for all. The camera moves with him, his hands threatening inwards from the side of the frame, an over-the-shoulder, almost-point-of-view shot signalling the pushing of the young Jedi towards the edge of the precipice. Think how many important showdowns or daring escapes happen on the edge of these apocalyptic canyons in George Lucas’ adventure serials (i.e. including the Indiana Jones films). Nothing signifies imminent doom better than a potential plummeting towards a vanishing point. These dangers of extreme vertical drops stand in sharp contrast to the horizontal axes of the chase scenes such as the one in the previous frame. Death comes when the forward motion stops.

An an unenlightened child, it always puzzled me why these mighty, wise warriors, good or evil, didn’t just kill each other. Instead they brandish statements like “give into your hatred” or “if you strike me down I shall become more powerful than you can possibly imagine”. Really? Do they want to be killed or not? What happened to the old ways of goodies and baddies trying to kill each other because each represented a threat to the other’s plans? And why did Darth Vader kill Obi-Wan Kenobi if he knew it would make him more powerful? Only later did I understand that the plan was to turn Luke Skywalker into an asset of evil and turn him to the Dark Side. This might seem like a spiritual conception of evil as a corrupting infection that requires a single transgressive act (tellingly centred around the killing of a feared enemy) to let the infection take over the body and mind, but it’s also a conservative one where you either are or are not wicked and get branded as such. In any case, by the end we still wind up with the Emperor preparing to kill Luke once and for all. The camera moves with him, his hands threatening inwards from the side of the frame, an over-the-shoulder, almost-point-of-view shot signalling the pushing of the young Jedi towards the edge of the precipice. Think how many important showdowns or daring escapes happen on the edge of these apocalyptic canyons in George Lucas’ adventure serials (i.e. including the Indiana Jones films). Nothing signifies imminent doom better than a potential plummeting towards a vanishing point. These dangers of extreme vertical drops stand in sharp contrast to the horizontal axes of the chase scenes such as the one in the previous frame. Death comes when the forward motion stops.

[See also

[See also

Violence as a way of achieving racial justice is both impractical and immoral. I am not unmindful of the fact that violence often brings about momentary results. Nations have frequently won their independence in battle. But in spite of temporary victories, violence never brings permanent peace. It solves no social problem: it merely creates new and more complicated ones. Violence is impractical because it is a descending spiral ending in destruction for all. It is immoral because it seeks to humiliate the opponent rather than win his understanding: it seeks to annihilate rather than convert. Violence is immoral because it thrives on hatred rather than love. It destroys community and makes brotherhood impossible. It leaves society in monologue rather than dialogue. Violence ends up defeating itself. It creates bitterness in the survivors and brutality in the destroyers. (

Violence as a way of achieving racial justice is both impractical and immoral. I am not unmindful of the fact that violence often brings about momentary results. Nations have frequently won their independence in battle. But in spite of temporary victories, violence never brings permanent peace. It solves no social problem: it merely creates new and more complicated ones. Violence is impractical because it is a descending spiral ending in destruction for all. It is immoral because it seeks to humiliate the opponent rather than win his understanding: it seeks to annihilate rather than convert. Violence is immoral because it thrives on hatred rather than love. It destroys community and makes brotherhood impossible. It leaves society in monologue rather than dialogue. Violence ends up defeating itself. It creates bitterness in the survivors and brutality in the destroyers. (