Steven Spielberg has owned the rights to the Tintin books since 1983, when they were passed to him by Hergé‘s widow. Apparently, the Belgian author was an admirer of Spielberg’s work, and had indicated that he was the only director who could do the stories justice. Presumably, both Spielberg and Hergé saw common ground between Tintin and Indiana Jones but, if I may be allowed to presume a little further, neither of them can have expected that the finished film would take nearly three decades, and be a fully-CG 3D motion-capture extravaganza on a budget of $130 million. For comparison, Raiders of the Lost Ark had been finished for $18 million, and Hergé’s death coincided with the release of MS Dos 2.0. But while the new film appears on a wave of publicity about its state-of-the art technology, it is also resolutely old-fashioned. Continue reading

Steven Spielberg has owned the rights to the Tintin books since 1983, when they were passed to him by Hergé‘s widow. Apparently, the Belgian author was an admirer of Spielberg’s work, and had indicated that he was the only director who could do the stories justice. Presumably, both Spielberg and Hergé saw common ground between Tintin and Indiana Jones but, if I may be allowed to presume a little further, neither of them can have expected that the finished film would take nearly three decades, and be a fully-CG 3D motion-capture extravaganza on a budget of $130 million. For comparison, Raiders of the Lost Ark had been finished for $18 million, and Hergé’s death coincided with the release of MS Dos 2.0. But while the new film appears on a wave of publicity about its state-of-the art technology, it is also resolutely old-fashioned. Continue reading

Category Archives: Special Effects

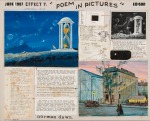

Norman O. Dawn Collection

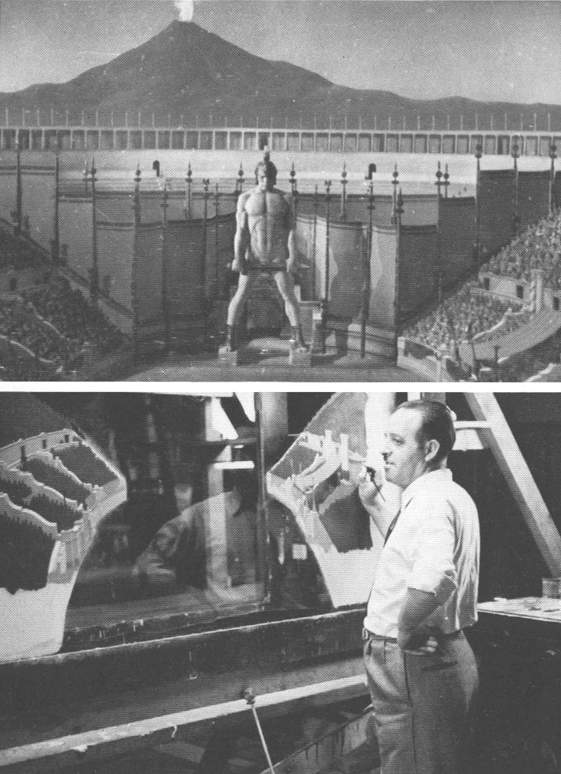

These wonderful cards are from the collection of Norman O. Dawn, as displayed at the Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin last year, as part of the special effects section of the Making Movies exhibition. Dawn was the creator of many innovative special effects for photography and film, most notably the glass shot, where the mise-en-scene is augmented by scenery painted onto a pane of glass that is placed between the camera and the set/location. Here’s an example of Byron Crabbe (who also worked on King Kong and The Most Dangerous Game before his untimely death in 1937) painting set extensions onto glass for a scene from The Last Days of Pompeii (1935):

[This image was taken from NZPete’s fabulous blog about old-school special effects, including matte painting, glass shots and the like. Pete has managed to round up an impressive array of images and info about the techniques and personnel that made so many extraordinary moments of Hollywood’s golden age.]

Dawn created these cards to record his array of techniques used on more than eighty films, and to illustrate them for the producers and executives who had to be convinced that such amazing illusions were possible. If nothing else, with their miniature watercolours, oil paintings, sketches and handwritten notes, they stand as testament to the artisanal, hands-on nature of early special effects.

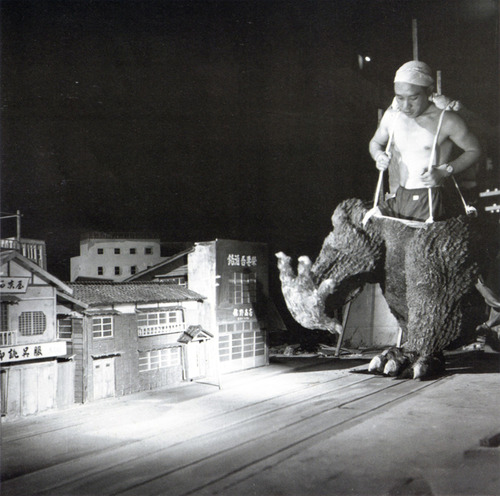

Fragment #24: The Invention of Godzilla

[In this extract from his book Eiji Tsuburaya: Master of Monsters, August Ragone describes the development of the eponymous monster for the original Japanese Gojira (1954), better known to international audiences as Godzilla.]

“They … wanted the film to reverberate with current geopolitical, national, and social concerns, as well as evoking the spectre of the Tokyo Fire Raids and the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. They agreed they should approach the film in earnest, treating it as they would any serious, real-life subject, rather than as a ‘monster movie’. The monster’s attack on Tokyo could be seen as an incarnation of war itself, and [executive producer, Iwao] Mori thought the creature should carry the physical scars of H-bomb tests.

Originally, [Eiji] Tsuburaya wanted to bring the nuclear nightmare to life using stop-motion effects, as King Kong had been made. When asked how long it would take to produce such effects, Tsuburaya told Mori it would take seven years to shoot all of the effects required by the screenplay, based on the current staff and infrastructure at Toho. Of course this was out of the question – the film had to be in theatres by the end of the year. Tsuburaya decided that his department’s considerable expertise in miniature building and visual effects photography could accommodate working with a live actor in a monster costume instead of using stop-motion techniques. Mori and Tanaka agreed and gave him the green light to proceed with planning and construction.

Planning was a painstaking process. To ensure that things would run smoothly, [director Ishiro] Honda and [writer Takeo Murata] would present scene ideas to Tsuburaya, who would tell them whether his team could pull them off. (More often than not, he told them he could.) Problematic scenes or shots were rooted out during the extensive storyboarding process, helping prevent costly mistakes during shooting.

Planning was a painstaking process. To ensure that things would run smoothly, [director Ishiro] Honda and [writer Takeo Murata] would present scene ideas to Tsuburaya, who would tell them whether his team could pull them off. (More often than not, he told them he could.) Problematic scenes or shots were rooted out during the extensive storyboarding process, helping prevent costly mistakes during shooting.

[…] To design the creature, Kayama suggested popular mangaka (comic book artist) Wasuke Abe, who had illustrated several of Kayama’s juvenile adventure stories and worked for numerous publishers and in many genres. Abe’s most famous work was Kenya Boy (Shonen Keniya), written by his brother, whose pen name was Shoji Yamagawa. The story, about an orphaned Japanese youth lost in Africa, was more Lost World than Tarzan, set in a land alive with prehistoric creatures. When Abe conferred with the Godzilla staff, he brought with him the current edition of Kenya Boy, which featured an encounter with a Tyrannosaurus Rex. This would prove to have a decisive influence on the production design of Godzilla. While Abe’s designs were ultimately rejected – they were more abstract and humanoid than animal, and the beast’s head was rendered like a mushroom cloud – he was retained to help draw the hundreds of storyboards required for the film.

Tanaka, Tsuburaya, and Honda decided to focus on an original dinosaur of their own design. Inspired by a Life magazine pictorial on prehistoric times featuring paintings by Rudolph Zallinger and by the celebrated Czech dinosaur artist Zdenek Burian, production designer Akira Watanabe combined attributes of the Tyrannosaurus Rex and the Iguanodon, and added the plates of the Stegosaurus. To bring Watanabe’s drawings to life, Tsuburaya contacted his old colleague from The War at Sea From Hawaii to Malaya, Teizo Toshimitsu. Toshimitsu took Watanabe’s drawings and began to render the creature in clay. After experimenting with scaly, warty, and alligator-skin textures, the staff agreed on the alligator version.

Toshimitsu and the staff of the visual-effects department began construction of a Godzilla suit for an actor to wear. The first version of the suit was built over a cloth-and-wire frame and layered with hot rubber, which was melted in a steel drum and applied in layers over the frame. This resulted in a heavy and immobile costume in which the actor could barely move, and so it was scrapped.

Toshimitsu and the staff of the visual-effects department began construction of a Godzilla suit for an actor to wear. The first version of the suit was built over a cloth-and-wire frame and layered with hot rubber, which was melted in a steel drum and applied in layers over the frame. This resulted in a heavy and immobile costume in which the actor could barely move, and so it was scrapped.

A second suit, while still incredibly heavy at 220 pounds, allowed more freedom of movement, and became the final costume. The first suit was cut into two sections and used for scenes requiring only a partial shot of the monster, and Toshimitsu also created a smaller-scale, mechanical, hand-operated puppet that could spray a stream of mist from its maw, to simulate the creature’s nuclear breath in close-ups. A young actor and stuntman, Haruo Nakajima, was given the part of Godzilla (a role he would play a number of times in a long career that found him frequently cast as a monster), alternating with fellow thespian Katsumi Tezuka, which allowed production to continue when Nakajima needed relief from the physicality demanding part.

[…] The first day of shooting miniature photography involved Godzilla’s destruction of the National Diet Building, Japan’s Parliament, which was built in 1/33 scale so that Godzilla would appear to tower over the structure. They decided to let Tezuka play the scene, Nakajima later recalled, but he fell flat and hit his jaw square on the miniature set, ruining the shot and necessitating retakes, this time with Nakajima in tight close-ups because Tsuburaya did not have time to rebuild the set.

The punishing role would bruise and scar both men. Stuffed into the stifling suit, roasting alive under the studio lights, they suffered from heat exhaustion and blackouts, and found themselves breathing fumes from burning rags soaked in kerosene, used to give the impression that Tokyo was ablaze. More than a cup of sweat was poured out of the suit after each scene was shot, and Nakajima ended up losing twenty pounds during the course of the production. On one of his rare days off, Nakajima received word that Tezuka and several crew members had nearly been electrocuted when a live wire fell into the indoor pool set. While using live actors was less time-consuming than tackling stop-motion animation, it was far from an easy shortcut, and involved long, arduous hours, often all-nighters.”

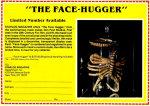

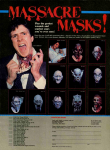

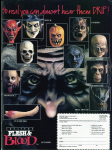

Fangoria Ads

Aside

Don’t ask why I decided to compile a gallery and slideshow of advertisements gathered from early issues of the horror magazine Fangoria. I don’t have a good answer. Rummaging through back issues looking for articles about prosthetics, special effects make-up and puppetry, I became a little distracted by the advertisements for video-cassettes (look how expensive it was, in the 1980s, to buy your own VHS tapes!), masks, books, t-shirts and gloopy, gory make-up effects. Ostensibly a journal celebrating the inventive evisceration of the human body, Fangoria actually comes across as a cheery community centre for enthusiasts of rubbery prosthetics and homemade horrors. You’ll find some familiar monsters in this gallery, and some lovely offers to help you simulate demonic possession, or a bit of limb-lopping, gut chewing dismemberment in the comfort of your own home. Avoid if more than a little squeamish. Otherwise, enjoy a bit of 80s nostalgia. Some of these offers may no longer be available, though. Sorry.

Final Call for Papers – Special Effects: New Histories, Theories, Contexts

Call for Papers!

The deadline for submission of abstracts is fast approaching. We’ve had some amazing submissions so far, from a variety of contributors, but there’s still time for a few more. Full details are below, but you can ask for more info if you need or want to know more…

Special Effects: New Histories, Theories, Contexts

Special Effects: New Histories, Theories, Contexts

Edited by Michael Duffy [Towson University], Dan North [University of Exeter], and Bob Rehak [Swarthmore College]

Deadline for Abstracts: 1 March 2011

Deadline for Submissions: 1 January 2012

Recent decades have seen ever more prominent and far-reaching roles for special and visual effects in film and other media: blockbuster franchises set in detailed fantasy and science-fiction worlds, visually experimental adaptations of graphic novels, performances in which the dividing lines between human and inhuman – even between live action and animation – seem to break down entirely. Yet the cinema of special effects, so often framed in terms of new digital technologies and aesthetics, actually possesses a complex and branching history, one that both informs and complicates our grasp of the “state of the art.” At stake in studies of special/visual effects is a more comprehensive understanding of film’s past, present, and future in an environment of shifting technologies and media contexts.

We seek contributions to a volume focused on special effects as aesthetic, industrial, and cultural practices, moving beyond formal analysis to a wider consideration of special effects’ historical roots and developmental paths, their underlying technologies and creators, and their intersection with other domains of art, commerce, and ideology. We are particularly interested in essays that elaborate on specific periods of change that special and visual effects have undergone over the course of their history. Although we welcome work that deals with digital technologies and contemporary cinema, we encourage contributors to contextualise recent developments in relation to broader histories of visual illusion and spectacular artifice.

The book will integrate an online forum to develop an extensive bibliography, web links to further reading, and a scholar/practitioner directory.

Possible topics might include, but are not limited to:

- Theoretical approaches to the study of special effects history and technique, including (but not restricted to) ‘ontology’ debates surrounding the interplay between analogue and digital technologies.

- Theories of spectatorship, visual illusions, and special effects.

- Critical histories/analyses of individual processes, e.g. matte paintings, compositing, bluescreen, the Independent Frame, miniatures, stop-motion animation, animatronics, prosthetics, motion capture, etc.

- Pre-visualization techniques, including production design, concept art, and animatics.

- The ongoing influence of effects pioneers including Georges Méliès, Segundo de Chomon, James Stuart Blackton, Emile Cohl, Albert E. Smith, R.W. Paul, and other makers of early ‘trick films’.

- Changes to studio structures and the evolution of the special-effects ‘house’.

- Industry “stars” such as Stan Winston, Douglas Trumbull, Richard Edlund, Tom Savini, Eiji Tsubuyara, Rick Smith, Ray Harryhausen, Willis O’Brien, John P. Fulton, John Gaeta, etc.

- The uses of special effects and spectacle in the experimental or avant-garde works of film-makers including Peter Tscherkassky, Stan Brakhage, Norman McLaren, etc.

- The significance of special effects in non-Hollywood, low-budget and independent cinema.

- Special-effects fandom, connoisseurship, and critique

- How animatronics, puppetry and make-up are adapted/reconstituted/re-contextualized for studio/franchise rebirths.

- Visual effects in television, video games, and transmedia.

- Spectacular uses of colour, widescreen, IMAX, and 3D processes.

- Self-reflexive uses of special effects as a commentary on the history/ontology of media.

Essays should run between 3000 and 6000 words in length. Send abstracts (title, 500 word description of project, and author bio) or requests for further information to: fxnewhistories@gmail.com

Editors can be contacted individually at:

- Michael Duffy [mduffy@towson.edu]

- Dan North [D.R.North@exeter.ac.uk]

- Bob Rehak [brehak1@swarthmore.edu]

Picture of the Week #65: The Execution of Mary Queen of Scots

Yes, I know it’s a video, not a ‘picture’, but to celebrate the birthday of Thomas Edison, here’s a barely appropriate reminder of The Execution of Mary Queen of Scots, filmed in New Jersey for the Edison Manufacturing Co. on 28th August 1895, by Alfred Clark. I could have chosen any number of Edison shorts to mark the man’s birthday, but this is a favourite of mine for its early use of a trick effect in a historical re-enactment. This is probably the first substitution cut, when the actor playing Mary (the Library of Congress lists this as one Robert Thomae) is replaced with a dummy for the moment of death. You can see the join, but it’s still quite skilfully done. This film would have been watched, one viewer at a time, on an Edison kinetoscope, and it apparently caused a bit of a stir, with some viewers allegedly fearing that somebody really had died for their art. I somehow doubt this, but it makes a nice story, and inaugurates the undying myth of the snuff film.

The film is not historically accurate – an eyewitness to the beheading on 7th February 1857 records that it took three strokes to decapitate Mary, while the film makes it all look smooth and easy. Right at the end of the film, you can see the executioner holding up her head for the watching crowd: this is most likely true; he also removed the head-dress from her severed head and revealed the secret that she’d hidden during her long imprisonment (19 years) at her cousin’s pleasure – her hair had turned completely white. Either that, or he dropped the head, having tried to pick it by the wig that Mary wore – accounts vary.

I’m not sure what involvement, if any, Edison himself had in the making of this film, but it definitely marked the start of an escalation in the sensational spectacles recorded for the kinetoscope. Alfred Clark made a few more grisly shorts, including The Burning of Joan of Arc, also produced in 1895. It reached a peak in 1903 with the notorious and self-explanatory Electrocuting an Elephant, which you can read about here: it’s a fascinating story, even if you don’t want to watch the film itself.

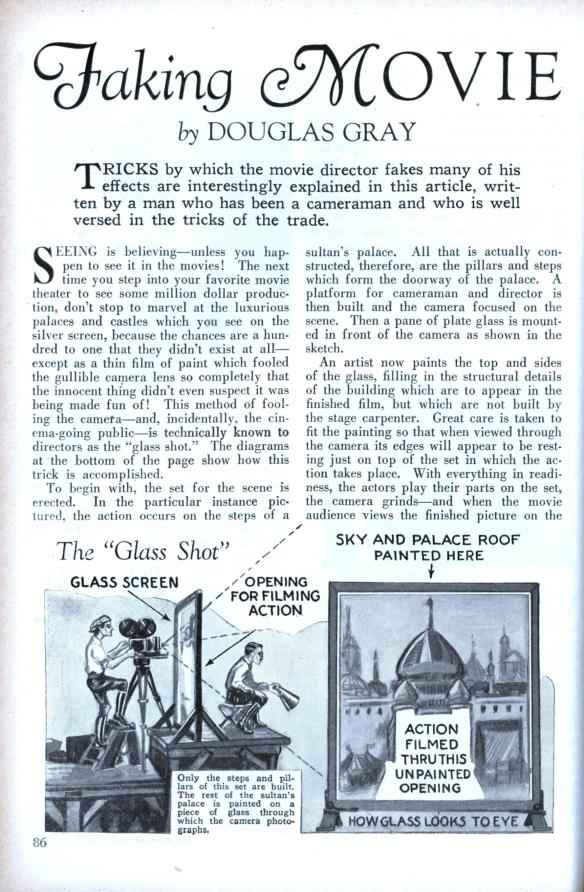

Picture of the Week #63: Faking Movie Scenes

This article from the January 1929 issue of Modern Mechanics reveals many secrets of film special effects, including glass shots, miniature models and stop-motion animation (“Naturally, the process was very tedious”). It might not teach you anything you didn’t know already, but it’s a great timepiece. You can find much more of this sort at the Modern Mechanix blog.

[Click on any page to enlarge.]

Virtual Actors, Spectacle and Special Effects in the Matrix Trilogy

[Credit for this post must be shared with a group of my final-year students at the University of Exeter. The assignment was to re-edit a piece of writing for re-publication online. I hadn’t tried this before, but wanted to experiment with collaborative work using Google docs. To begin with, I posted the first draft of an essay I wrote in 2003, the first book chapter I ever had published (the finished product had ended up in The Matrix Trilogy: Cyberpunk Reloaded, edited by Stacy Gillis and published by Wallflower Press in 2005). The task was to re-edit a 6000-word essay to about half that length, correcting errors, adding web-links and images, removing academic jargon and generally formatting it for an online readership (however they might interpret such a thing). There were 28 students on the module, and each had access to the document – the only rules were that other students’ edits should be respected: if you wished to change something that had already been reworded, you should add a comment to say why. The integrity, argument, grammar, tone and style of the original text demanded no such respect, and was to be disregarded completely. Almost every sentence has been altered in some way. More than 3000 words have been excised, either by making my youthful, eagerly excessive prose more succinct, or by hacking out wholesale paragraphs that distracted from the central argument. I wouldn’t want to have them treat another writer’s work in this way, and the essay was mostly concerned with close reading, clarifying an argument, addressing a different audience and working collaboratively, so in future, I’ll give this another go and divide students into smaller groups and let them work together to build a blog post from the ground up rather than just cleaning up my old messes. It was a very interesting process to watch, and I hope they also found it productive/instructive. The results are posted below.]

[Credit for this post must be shared with a group of my final-year students at the University of Exeter. The assignment was to re-edit a piece of writing for re-publication online. I hadn’t tried this before, but wanted to experiment with collaborative work using Google docs. To begin with, I posted the first draft of an essay I wrote in 2003, the first book chapter I ever had published (the finished product had ended up in The Matrix Trilogy: Cyberpunk Reloaded, edited by Stacy Gillis and published by Wallflower Press in 2005). The task was to re-edit a 6000-word essay to about half that length, correcting errors, adding web-links and images, removing academic jargon and generally formatting it for an online readership (however they might interpret such a thing). There were 28 students on the module, and each had access to the document – the only rules were that other students’ edits should be respected: if you wished to change something that had already been reworded, you should add a comment to say why. The integrity, argument, grammar, tone and style of the original text demanded no such respect, and was to be disregarded completely. Almost every sentence has been altered in some way. More than 3000 words have been excised, either by making my youthful, eagerly excessive prose more succinct, or by hacking out wholesale paragraphs that distracted from the central argument. I wouldn’t want to have them treat another writer’s work in this way, and the essay was mostly concerned with close reading, clarifying an argument, addressing a different audience and working collaboratively, so in future, I’ll give this another go and divide students into smaller groups and let them work together to build a blog post from the ground up rather than just cleaning up my old messes. It was a very interesting process to watch, and I hope they also found it productive/instructive. The results are posted below.]

The proliferation of behind-the-scenes material and revelation of the technologies behind the effects offsets any conviction in the illusion suggested by photorealistic CGI. At the most cynical level, this is in the service of selling DVDs with the promise of privileged secrets, or of attracting hits to members-only sections of websites, but it also keeps the spectator engaged with the diegetic technologies as reflections or extrapolations of extra-filmic developments in digital imaging. Consequently, by finding new ways to engage with the profilmic aspects of the Matrix trilogy, the spectator becomes an active participant in the process of reinforcing the illusion of virtual reality offered by the trilogy’s diegesis. The spectator’s desire to enter the virtual world encountered onscreen is made possible through the paratextual features found on the DVD release, which situate the film as merely one medium by which the Matrix may be explored; indeed, as Chuck Tryon has noted, ‘the film itself serves primarily as a means of stimulating interest in the wider media franchise, one that extends well beyond the DVD itself into other ancillary materials’ (29). The digressive aspects of the film serve to preserve the function of special effects to draw attention to themselves without necessitating compromises in technical clarity and perceptual realism.

The Burly Brawl

‘The Burly Brawl’ refers to a scene midway through Reloaded in which Neo fights an ever-expanding army of Smiths, the rogue agent who has acquired the ability to clone himself. Initiated by a scuffle with a few agent replicas, the scene employs special effects to primarily remove wires and to digitally graft Agent Smith’s visage on to the faces of each stunt performer. As Neo is called upon to parry the attacks of increasing number Smiths, so the visual effects are required to replace more of the combatants with computer-generated doubles. This challenges the spectator to discern the points at which the switches occur, urging the viewer to contemplate the discrepancy between real and rendered.

The scene also serves self-consciously as a showcase for ‘Virtual Cinematography,’ the conglomeration of digitally-rendered bodies and backgrounds offering a theoretically unlimited number of shooting angles within that virtual space. Before ‘Virtual Cinematography’ became the technical buzzword surrounding the films, The Matrix offered its viewers the signature visual trope of ‘bullet-time,’ an effect of camera movement within ultra-slow motion which, despite occupying no more than twenty seconds of screen time in the first film, was instrumental in establishing the film as technically innovative. In bullet-time effects, the human subject is first recorded against a green screen by the rig of up to 120 cameras set to shoot in rapid sequence, providing a series of still images of the action (see Figure 1) Such a novel, seemingly unique effect might be seen as working against the intertextual digressions we have suggested are prompted by the appearance of a technical illusion – how does the spectator find an intertext for something that has never been witnessed before?

Bolter and Grusin have argued that new media forms exist only in relation to earlier configurations of techniques and technologies (50). The innovative bullet-time sequences used in the Matrix trilogy are a recent illustration of existing technologies narrativised and branded as a novel visual spectacle. Another example is The Campanile Movie (1997), Paul Debevec’s 150-second fly-by of the Berkeley campus (see video above), where textures of the buildings captured from still photographs were mapped onto three dimensional representations of their actual geometry thereby allowing the creation of virtual backdrops into which the human subjects could be composited. Similarly, Dayton Taylor’s ‘Timetrack’ camera rig, which had been patented in 1997 and tested on several television commercials, sired the means of capturing the ultra-slow motion foreground action; we could even trace such multi-camera experiments as far back as the motion studies conducted in California in the 1870s by Eadweard Muybridge (right),“the man who split the second,” as Rebecca Solnit would have it (7). Even though the vast majority of viewers would not have had prior knowledge of these experiments in the history of remediation, it is unlikely that they had never experienced the kinds of hyperbolic spatio-temporal manipulations they inspired. If the Matrix films give the impression of novelty, it is only an illusion created by the prolific remediation of a wide variety of pop cultural reference points; they have appropriated certain qualities of kung fu films, comic book visuals, anime compositions and anti-corporate nu-metal posturing, technologised as if to proclude their imposition upon the new texts. The early version of bullet-time was not fully virtualised because it required detailed pre-planning from conceptual drawings by comic book illustrators Steve Skroce and Geof Darrow (Lamm 8) to computer-generated pre-visualisations of shots, followed by strict adherence to those plans at the shooting stage. The virtual camera was constrained, its very virtuality a cunning illusion. In one piece of explication/publicity, visual effects supervisor John Gaeta promises that the sequels’ virtual cinematography was more advanced, allowing the construction of shots to be devised regardless of camera position and possible lines of movement:

Similarly, Dayton Taylor’s ‘Timetrack’ camera rig, which had been patented in 1997 and tested on several television commercials, sired the means of capturing the ultra-slow motion foreground action; we could even trace such multi-camera experiments as far back as the motion studies conducted in California in the 1870s by Eadweard Muybridge (right),“the man who split the second,” as Rebecca Solnit would have it (7). Even though the vast majority of viewers would not have had prior knowledge of these experiments in the history of remediation, it is unlikely that they had never experienced the kinds of hyperbolic spatio-temporal manipulations they inspired. If the Matrix films give the impression of novelty, it is only an illusion created by the prolific remediation of a wide variety of pop cultural reference points; they have appropriated certain qualities of kung fu films, comic book visuals, anime compositions and anti-corporate nu-metal posturing, technologised as if to proclude their imposition upon the new texts. The early version of bullet-time was not fully virtualised because it required detailed pre-planning from conceptual drawings by comic book illustrators Steve Skroce and Geof Darrow (Lamm 8) to computer-generated pre-visualisations of shots, followed by strict adherence to those plans at the shooting stage. The virtual camera was constrained, its very virtuality a cunning illusion. In one piece of explication/publicity, visual effects supervisor John Gaeta promises that the sequels’ virtual cinematography was more advanced, allowing the construction of shots to be devised regardless of camera position and possible lines of movement:

We wanted to create scenes that were not in any way restricted by physical placement of cameras. … We wanted longer, flowing shots that built action to a level where the interactions of bodies would be so complex there would be no way that we could properly conceive of the cameras during shooting. Instead, we would create the master template for the choreography, and then have complete flexibility to compose shots in postproduction.’ (quoted in Fordham 87)

Gaeta claims that the virtual camera technology was supposed to mirror the way the technology in the film created an enforced hallucination in the Matrix whilst existence continued outside of it. The Matrix films thematise technology in ways which are not unfamiliar within discourses around science fiction and cyberpunk cinema, but the visual effects serve to knit the components of the franchise together as a transmedia experience, and go beyond the usual spectacular functionings of such illusions to solidify the connections between the diegetic and extra-filmic technologies. For instance, the presence of virtual actors within the films is more than a technical anomaly necessitated by the limits of human performance, but a fully integrated trope mobilising discursive elements within and without the text. The virtual actor was also the result of discussions of superhumanism between the Wachowskis and John Gaeta: “Within the Matrix, everything is really a state of mind, a mental self-actualization of your abilities. We wanted to visually depict that power, simulating events that Neo was part of.” (quoted in Fordham 86)

Virtual Actors and Cinematic Bodies

It would be easy to believe that the age of the synthespian is imminent, and that soon human actors will interact with computer-generated co-stars without the audience realising which is which. Will Anielewicz, a senior animator at effects house Industrial Light and Magic, promised recently that “Within five years, the best actor is going to be a digital actor” (quoted in Baylis). The apotheosis of an animated character into an artificially intelligent, fully simulacrous figure indistinguishable from its human referent is technically impossible, at least in the foreseeable future, but visual effects are not definitive renderings of a character or event, but indicators of ‘the state-of-the-art’ offering “a hint of what is likely to come” (Kerlow 1) in the field of visual illusions in the future. It is understandable that such a competitive industry needs to maintain interest in the potential of its products, but the mythos of the virtual actor has pervaded the Hollywood blockbuster in recent years; however, whereas in the pastthe computer-generated body had to fit into the diegesis unobtrusively, more recent films such as Avatar have moved away from the dichotomy of human and synthespian by fusing the marvels of CGI with the gestures, expressions and voices of real actors, creating immersive virtual worlds in which there is no tell-tale seam between illusion and reality. The seamless nature of this combination is still reliant on the actor’s performance to bridge the gap between the virtual and the actual by providing the digital body with a soul.

The Animatrix also explores uses of the virtual body – the CGI striptease which opens The Final Flight of the Osiris announces itself as ‘advanced’ by lingering on detailed surfaces of athletic bodies in action, drawing focus onto the technology which created it.Keen-eyed viewers might notice that Jue exhibits what might be the world’s first sighting of CG cellulite – the markings of a true body without the idealised gloss of airbrushed skin. Thus the desire for computers to create an ever more realistic “digital actor” has developed to include the imperfections of the human body. Jue’s movements were created from a combination of motion-capture from live actors, and ‘key-frame’ animation directed by computer animators. Unlike other CGI/human constructs such as Gollum in the Lord of the Rings trilogy or Jar Jar Binks in The Phantom Menace, in The Matrix trilogy, the virtual body provides a visual articulation of posthuman transcendence which confers fantastic capabilities upon the diegetic body and simultaneously imagines a liberated future for the cinematic body. No longer constrained by the limitations of the recording medium, the director is free to experiment with techniques such as ‘bullet time’ and the ‘virtual camera’ in order to present us with a world that, whilst clearly impossible in its flouting of the laws of physics or the death-defying stunts of its characters, nonetheless derives verisimilitude from its status as an autonomous entity; though impossible in our world, the removal of the spectator to a new, often techno-futurist reality eliminates the awkward juxtaposition of real/illusory as we struggle to reconcile what our eyes tell us with what our mind knows about the world we inhabit.Neo takes on the properties of a digitally cinematic body – he is preternaturally fast, fluid and precise in his movements. Through centring Neo in the onscreen action (Figure 2) and the use of digital effects (notably slow motion), Neo becomes both a powerful character within the story of a digital simulation and also a star perfomer within a filmic space. We could say that he is becoming synergised – he can assume the capacities of a computer game sprite or a synthespian, replicable and spectacular just by virtue of his very existence (as opposed to by virtue of what he actually does). His individual skill sets are downloaded as if they were applications for a smart phone, and it is within the realm of the Matrix that characters can use these skills to manipulate their bodies and appearances (what Morpheus calls “residual self image”), enabling them to become glamourised upgrades of their organic forms, which are prostrate elsewhere, grimy and linen-clad. The digital avatar, built from motion capture data, is a cinematic prosthesis which enables the performer to enact cinematisation directly, rather than through the use of tactical editing and careful composition which can, for instance, hide the face of a stunt double. The Brawl toys with viewers’ expectations about how an action sequence usually has to work around the limitations of the body. Virtual camera moves are only recognisable as such because we are familiar with where and how a camera can and cannot be moved.

When asked about similarities between the Burly Brawl and the climactic battle between the Bride and the Crazy 88 gang in his Kill Bill Volume I (2003), Quentin Tarantino was keen to distance himself from such “CGI bullshit,” even though his fight scene is as much a cinematic construction as any in the Matrix: “You know, my guys are all real. There’s no computer fucking around. I’m sick to death of all that shit. This is old school, with fucking cameras. If I’d wanted all that computer game bullshit, I’d have gone home and stuck my dick in my Nintendo” (quoted in Dinning 91). Tarantino objects to the over-use of CGI, but forgets that one of the reasons for the deployment of such “profane” digital imagery in the Matrix films is precisely for the purposes of differentiation from the films to which it refers (or pays homage). Yuen Woo-Ping served as a martial arts advisor on both the Kill Bill and the Matrix series, but the combat between Neo and Smith represents a dramatic remediation of the choreography for which he is renowned, rather than the generic authenticity for which he was enlisted by Tarantino. The Burly Brawl is built up from a series of actions appropriated from the kung fu film’s generic database, hyperbolised, digitised and virtualised. David Bordwell refers to the kung fu film’s use of “expressive amplification,” whereby “film style magnifies the emotional  dynamics of the performance” (232). Therefore, combatants in kung fu films can appear to fight with superhuman speed (under-cranking the camera during shooting makes the projected film run slightly faster), skill (supporting wires can help them to defy gravity) and strength (power powder sprinkled on clothing, coupled with sound effects, accentuates the visual and sonic impact of a blow). The Brawl remediates what Bordwell terms the “one-by-one tracking shot,” a technique of cinematic authentication through which a fighter is shown moving through a group of combatants in a continuous take. The length of the unedited shot cues the spectator to accept that the performer is demonstrating a sustained sequence of skills. During the Burly Brawl, two such shots occur, the first performed by Keanu Reeves and a group of stunt performers, the second by his digital double. Subjecting the real and virtual bodies to the same modes of mediation helps foster the viewer’s fascination with a discrepancy between the two. Throughout the Brawl, the spectator is incited to distinguish between them, just as the kung fu fanatic will inspect the text for evidence of the star’s authenticity or replacement by a diegetically anomalous but technically necessitated stunt double. The trilogy constructs a dialectic between old and new by remediating kung fu motifs and visual stylings; for instance, the pedagogic dojo fight sequence, wirework and choreographed combat. When Keanu’s digital copy flies through the air, the illusion is distinct because the virtual body is unfettered by the need for physical reference – wirework always exhibits the body’s need for balanced weight distribution, providing its distinctive, super-real look.

dynamics of the performance” (232). Therefore, combatants in kung fu films can appear to fight with superhuman speed (under-cranking the camera during shooting makes the projected film run slightly faster), skill (supporting wires can help them to defy gravity) and strength (power powder sprinkled on clothing, coupled with sound effects, accentuates the visual and sonic impact of a blow). The Brawl remediates what Bordwell terms the “one-by-one tracking shot,” a technique of cinematic authentication through which a fighter is shown moving through a group of combatants in a continuous take. The length of the unedited shot cues the spectator to accept that the performer is demonstrating a sustained sequence of skills. During the Burly Brawl, two such shots occur, the first performed by Keanu Reeves and a group of stunt performers, the second by his digital double. Subjecting the real and virtual bodies to the same modes of mediation helps foster the viewer’s fascination with a discrepancy between the two. Throughout the Brawl, the spectator is incited to distinguish between them, just as the kung fu fanatic will inspect the text for evidence of the star’s authenticity or replacement by a diegetically anomalous but technically necessitated stunt double. The trilogy constructs a dialectic between old and new by remediating kung fu motifs and visual stylings; for instance, the pedagogic dojo fight sequence, wirework and choreographed combat. When Keanu’s digital copy flies through the air, the illusion is distinct because the virtual body is unfettered by the need for physical reference – wirework always exhibits the body’s need for balanced weight distribution, providing its distinctive, super-real look.

The Matrix films have presented a series of postulations on the past and future of special effects. Virtual cinematography is defined in relation to earlier, less technologised forms of cinema (kung fu, anime) by remediating their motifs of physical or animated display in the service of a technological spectacle. However, it also offers a ‘utopian’ idea of a cinema free from the tethers of indexicality and practical constraints. This liberation is reflected in Neo’s empowerment as a virtualised body, free from the gravitational and physical restrictions of the real world.One must keep in mind though, that since this fiction always exists as a redesigning of existing reference points, the concept of virtual cinematography is, for the time being, only an illusion of what the future holds. The spectator is empowered with mastery of the film text by a profusion of textual exit points, which offer the chance to observe the spectacle from a remove that reveals its artificiality, while simultaneously celebrating the seductive force of its artifice.

Bibliography

- Baylis, Paul. “Weekend Beat: In quest of the ‘holy grail’ of the truly lifelike digital actor.” 7 June 2003.

- Bordwell, David. Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment. Harvard: Harvard UP, 2000.

- Bolter, Jay David and Richard Grusin. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2000.

- Buckland, Warren. “Between Science Fact and Science Fiction: Spielberg’s Digital Dinosaurs, Possible Worlds, and the New Aesthetic Realism.” Screen 40:2 (Summer 1999): 177-192.

- Bukatman, Scott. Terminal Identity: The Virtual Subject in Postmodern Science Fiction. Durham: Duke UP, 1993.

- Dinning, Mark. “The Big Boss.” Empire 14:11 (November 2003): 84-92.

- Fordham, Joe. “Neo Realism.” Cinefex 95 (October 2003): 84-127.

- Hunt, Leon. Kung Fu Cult Masters. London: Wallflower, 2003.

- Kerlow, Isaac V. “Virtual CG Characters in Live-Action Feature Movies.” 19 November 2003.

- Klein, Norman M. The Vatican to Vegas: A History of Special Effects. New York : The New Press, 2004.

- Klinger, Barbara. “Digressions at the Cinema: Reception and Mass Culture.” Cinema Journal 28:4 (Summer 1989): 3-19.

- Lamm, Spencer, ed. 2000. The Art of The Matrix. New York : Newmarket Press.

- Pierson, Michele. Special Effects: Still in Search of Wonder. New York : Columbia UP, 2002.

- Prince, Stephen. “True Lies: Perceptual Realism, Digital Images and Film Theory.” Film Quarterly 49:3 (Spring 1996): 27-37.

- Sconce, Jeffrey. Haunted Media: Electronic Presence from Telegraphy to Television. Durham: Duke UP, 2000.

- Sellors, Paul C. “The Impossibility of Science Fiction: Against Buckland’s Possible Worlds.” Screen 41:2 (Summer 2000): 203-216.

- Solnit, Rebecca. Motion Studies: Time, Space and Eadweard Muybridge. London: Bloomsbury, 2003.

- Wood, Aylish. “Timespaces in Spectacular Cinema: Crossing the Great Divide of Spectacle Versus Narrative.” Screen 43:4 (Winter 2002): 370-386.

Enter the Void: Build Your Own Review

It’s the New Year, and I’ll start as I mean to go on – by finishing the stuff I failed to complete in 2010, including this post about Enter the Void, a late consideration of its cinema release, but way ahead of its appearance on DVD in the UK (you’ll have to wait until April). If it wasn’t divisive, it wouldn’t be a Gaspar Noé film, so Enter the Void is a prime candidate for a Build Your Own Review post, especially since I’m not even sure of my own responses to it. I found it a mix of fascination and frustration, ultimately a grand folly, by turns spectacular and dull; even though I looked back on it the next day with more appreciation for its ambitions, it’s meant to be an overwhelming, enveloping sensory experience, and it just didn’t do its job on my brain. So, here are some split-personality thoughts on the film, some of them mine, some of them from other critics. Please feel free to offer up your own views on the film in the comments box below.

The Boy With the Cuckoo-Clock Heart

While you’re waiting impatiently for Martin Scorsese’s Hugo Cabret (due for release on 9th December 2011), you might like to note the progress of The Boy With the Cuckoo-Clock Heart: at least, that seems to be the current English-language title – the film is adapted from a novella by Mathias Malzieu, though it started out as La mécanique du cœur, a 2007 concept album by Malzieu’s band Dionysos. Malzieu will co-direct the animated film version with Stéphane Berla (who has directed several videos for the band), reuniting the voice-cast who appeared in various roles on the album; this will include Eric Cantona, Rossy de Palma, Alain Bashung and Jean Rochefort, who plays the French film pioneer and Spectacular Attractions stalwart, Georges Méliès. You can see one of Berla’s music videos for Dionysos’s song Le Homme sans Trucage, featuring Rochefort, at the bottom of this post, but the film’s animation is expected to be closer to a CG version of Tim Burton’s The Corpse Bride, one of the band’s most often cited inspirations for its spindly gothic aesthetic. Luc Besson is producing, and the film is set for a French release in October 2011. I’ll keep an eye on this one (I’m beginning preliminary search for an essay on filmic representations of Melies), and let you know more as I find out: will it feature all of Dinysos’s songs, for instance? Will it be family friendly, or will it keep all of the books (obvious) phallic symbolism and the tune ‘Cunnilingus mon Amour’?