A (very brief) account of the invention of the Daguerreotype photographic system developed by Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre (1787 – 1851), as featured in Camera Comics #005 (1945). To see some examples of the stunning results visit the galleries of the Daguerreian Society, or click on the examples of modern Daguerreotypes produced by the artist Chuck Close at the bottom of this post.

Tag Archives: History

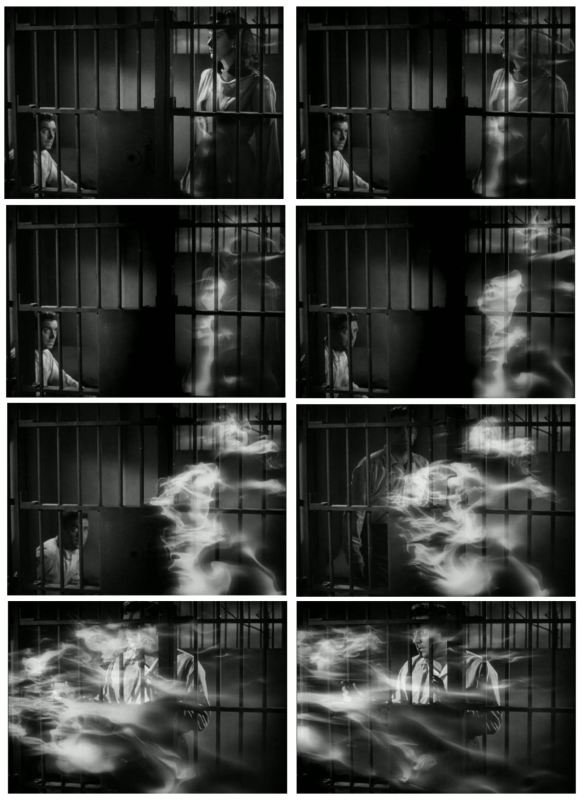

Picture of the Week #69: F.W. Murnau’s Four Devils

It is eighty years to the day since the great German director F.W. Murnau died from injuries sustained in a car crash at the age of 42, a week before the premiere of his final film, Tabu. As a small tribute, my Picture of the Week is a set of images related to Four Devils, his tale of a troupe of orphaned trapeze artists, which has the dubious honour of being one of the most famous lost films of all time. Premiered in 1928 (with a sound version released the following year), the film re-teamed Murnau with his Sunrise star Janet Gaynor (the first ever winner of the Academy Award for Best Actress, who was herself near-fatally injured in a car crash in 1982), but has not been seen since (allegedly), her co-star Mary Duncan lost the only print, which she had borrowed from Fox Studios.

Perhaps the closest you can get to seeing Four Devils is Janet Bergstrom’s excellent documentary Traces of Lost Film, which re-tells the story using the fragments it left behind in publicity photographs and design sketches:

http://www.dailymotion.com/swf/video/x4w9ou?width=560&theme=eggplant&foreground=%23CFCFCF&highlight=%23834596&background=%23000000

Final Call for Papers – Special Effects: New Histories, Theories, Contexts

Call for Papers!

The deadline for submission of abstracts is fast approaching. We’ve had some amazing submissions so far, from a variety of contributors, but there’s still time for a few more. Full details are below, but you can ask for more info if you need or want to know more…

Special Effects: New Histories, Theories, Contexts

Special Effects: New Histories, Theories, Contexts

Edited by Michael Duffy [Towson University], Dan North [University of Exeter], and Bob Rehak [Swarthmore College]

Deadline for Abstracts: 1 March 2011

Deadline for Submissions: 1 January 2012

Recent decades have seen ever more prominent and far-reaching roles for special and visual effects in film and other media: blockbuster franchises set in detailed fantasy and science-fiction worlds, visually experimental adaptations of graphic novels, performances in which the dividing lines between human and inhuman – even between live action and animation – seem to break down entirely. Yet the cinema of special effects, so often framed in terms of new digital technologies and aesthetics, actually possesses a complex and branching history, one that both informs and complicates our grasp of the “state of the art.” At stake in studies of special/visual effects is a more comprehensive understanding of film’s past, present, and future in an environment of shifting technologies and media contexts.

We seek contributions to a volume focused on special effects as aesthetic, industrial, and cultural practices, moving beyond formal analysis to a wider consideration of special effects’ historical roots and developmental paths, their underlying technologies and creators, and their intersection with other domains of art, commerce, and ideology. We are particularly interested in essays that elaborate on specific periods of change that special and visual effects have undergone over the course of their history. Although we welcome work that deals with digital technologies and contemporary cinema, we encourage contributors to contextualise recent developments in relation to broader histories of visual illusion and spectacular artifice.

The book will integrate an online forum to develop an extensive bibliography, web links to further reading, and a scholar/practitioner directory.

Possible topics might include, but are not limited to:

- Theoretical approaches to the study of special effects history and technique, including (but not restricted to) ‘ontology’ debates surrounding the interplay between analogue and digital technologies.

- Theories of spectatorship, visual illusions, and special effects.

- Critical histories/analyses of individual processes, e.g. matte paintings, compositing, bluescreen, the Independent Frame, miniatures, stop-motion animation, animatronics, prosthetics, motion capture, etc.

- Pre-visualization techniques, including production design, concept art, and animatics.

- The ongoing influence of effects pioneers including Georges Méliès, Segundo de Chomon, James Stuart Blackton, Emile Cohl, Albert E. Smith, R.W. Paul, and other makers of early ‘trick films’.

- Changes to studio structures and the evolution of the special-effects ‘house’.

- Industry “stars” such as Stan Winston, Douglas Trumbull, Richard Edlund, Tom Savini, Eiji Tsubuyara, Rick Smith, Ray Harryhausen, Willis O’Brien, John P. Fulton, John Gaeta, etc.

- The uses of special effects and spectacle in the experimental or avant-garde works of film-makers including Peter Tscherkassky, Stan Brakhage, Norman McLaren, etc.

- The significance of special effects in non-Hollywood, low-budget and independent cinema.

- Special-effects fandom, connoisseurship, and critique

- How animatronics, puppetry and make-up are adapted/reconstituted/re-contextualized for studio/franchise rebirths.

- Visual effects in television, video games, and transmedia.

- Spectacular uses of colour, widescreen, IMAX, and 3D processes.

- Self-reflexive uses of special effects as a commentary on the history/ontology of media.

Essays should run between 3000 and 6000 words in length. Send abstracts (title, 500 word description of project, and author bio) or requests for further information to: fxnewhistories@gmail.com

Editors can be contacted individually at:

- Michael Duffy [mduffy@towson.edu]

- Dan North [D.R.North@exeter.ac.uk]

- Bob Rehak [brehak1@swarthmore.edu]

Picture of the Week #65: The Execution of Mary Queen of Scots

Yes, I know it’s a video, not a ‘picture’, but to celebrate the birthday of Thomas Edison, here’s a barely appropriate reminder of The Execution of Mary Queen of Scots, filmed in New Jersey for the Edison Manufacturing Co. on 28th August 1895, by Alfred Clark. I could have chosen any number of Edison shorts to mark the man’s birthday, but this is a favourite of mine for its early use of a trick effect in a historical re-enactment. This is probably the first substitution cut, when the actor playing Mary (the Library of Congress lists this as one Robert Thomae) is replaced with a dummy for the moment of death. You can see the join, but it’s still quite skilfully done. This film would have been watched, one viewer at a time, on an Edison kinetoscope, and it apparently caused a bit of a stir, with some viewers allegedly fearing that somebody really had died for their art. I somehow doubt this, but it makes a nice story, and inaugurates the undying myth of the snuff film.

The film is not historically accurate – an eyewitness to the beheading on 7th February 1857 records that it took three strokes to decapitate Mary, while the film makes it all look smooth and easy. Right at the end of the film, you can see the executioner holding up her head for the watching crowd: this is most likely true; he also removed the head-dress from her severed head and revealed the secret that she’d hidden during her long imprisonment (19 years) at her cousin’s pleasure – her hair had turned completely white. Either that, or he dropped the head, having tried to pick it by the wig that Mary wore – accounts vary.

I’m not sure what involvement, if any, Edison himself had in the making of this film, but it definitely marked the start of an escalation in the sensational spectacles recorded for the kinetoscope. Alfred Clark made a few more grisly shorts, including The Burning of Joan of Arc, also produced in 1895. It reached a peak in 1903 with the notorious and self-explanatory Electrocuting an Elephant, which you can read about here: it’s a fascinating story, even if you don’t want to watch the film itself.

Fragment #9: Youssef Ishaghpour discusses History with Jean-Luc Godard

Youssef Ishaghpour: Your film [Histoire(s) du Cinéma] is like the century’s great novels, or poetic works intended to be complex and inclusive, blurring the distinction between prose and poetry, image and reflection, personal lyricism and documentary history, and systematically combining writing and re-memorisation to become the place where the truth of the century resounds. […] You are there alongside the other cinéastes and among them. You are also the museum attendant who expects his tip and berates visitors who don’t understand that the works are what it’s all about. You are the cantor, the orchestral conductor or high priest behind his lectern evoking the old films brought into the present by Langlois. You are also the one who owes his identity and his history to cinema and must repay the debt for his own salvation, and although you say “History, not its narrator“, you are there as the narrator, not just as the absent fabricator who has placed a card on display. You are also there as one who has been to heaven. One can’t help wondering whether Godard, who has found his home in cinema, occupies a place in your Histoire(s) equivalent to Hegel’s place in his system.

Jean-Luc Godard: History is stating something at a given moment, and Hegel puts it well when he says you’re trying to paint gray on gray. From what little I know of Hegel, what I like about his work is that for me he’s a novelist of philosophy, there’s a lot of romantic in him… […] To me History is, so to speak, the work of works; it contains all of them. History is the family name, there are parents and children, literature, painting, philosophy … let’s say History is the whole lot. So a work of art, if well made, is part of History, if intended as such and if this is artistically apparent. You can get a feeling through it because it is worked artistically. Science doesn’t have to do that, and other disciplines haven’t done it. It seemed to me that History could be a work of art…

[…]

Youssef Ishaghpour: Only cinema can narrate History with a capital H simply by telling its own history, the other arts can’t.

Jean-Luc Godard: Because it’s made from the same raw material as History. The fact is that even when it’s recounting a slight Italian or French comedy, cinema is much more the image of the century in all its aspects than some little novel; it’s the century’s metaphor. In relation to History, the most trivial clinch or pistol shot in cinema is more metaphorical than anything literary. Its raw material is metaphorical in itself. Its reality is already metaphorical. It’s an image on the scale of the man in the street, not the infinitely small atomic scale or the infinitely huge galactic one. What it has filmed most is men and women of average age. In a place where it is in the living present, cinema addresses them simply: it reports them, it’s the registrar of History. It could be the registrar, and if the the right scientific research were done afterwards it would be a social support; it wouldn’t neglect the social side.

Jean-Luc Godard & Youssef Ishaghpour. Cinema: The Archeology of Film and the Memory of a Century. Translated by John Howe. Oxford & New York: Berg, 2005. pp.26-8, 87-8

Dr Livingstone, I Consume?

Visitors to the David Livingstone Centre in Lanarkshire, Scotland will have had trouble failing to notice the large bronze sculpture of the famous explorer being chomped on by a lion. This was based on an actual incident in 1844 where Livingstone shot a lion that had just killed a woman in the village of Mabotsa, in what is now South Africa, where he had been serving as a missionary. Before it keeled over and died the enraged cat managed to leave some serious, permanent teethmarks in the shooter’s arm, which was never the same again. What we don’t see is the African teacher who distracted the lion away its meal and himself suffered severe injuries, saving Livingstone’s life in the process. This dramatic scene, enshrining the explorer’s courageous credentials (see how the natives fall helplessly to the ground!), was designed by none other than Ray Harryhausen, a fond favourite here at Spectacular Attractions, creator of stop-motion animation sequences for films like The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, It Came from Beneath the Sea, Earth vs the Flying Saucers, Jason and the Argonauts, The Golden Voyage of Sinbad, Clash of the Titans… In partnership with his wife Diana, who is Livingstone’s great-granddaughter, Harryhausen funded the statue and crafted a miniature version to be built by sculptor Gareth Knowles, who worked on it for four years before it was unveiled in 2004.

If you’ve ever seen any of Harryhausen’s miniature model figures on display, you’ll have noticed that most of them are sustained on dynamic poses, about to attack or be attacked. His mythical beasts are, more often than not, built for combat, and their physical properties are best displayed when grappling with other creatures or when precisely composited with human co-stars, some of whom are bound to get picked up and chewed at some point.

The Livingstone statue has much of the old-fashioned adventurism of his earlier work, celebrating dangerous encounters by staging them as pitched battles of strained sinew and flesh-tearing weaponry. But at least it shows, long after he retired (following Clash of the Titans, in 1983), that he still has an animator’s eye for a static scene that could at any moment be brought to life – every element is caught in mid-motion: not about to pounce, fall or claw, but pouncing, falling, clawing.