In some of my earlier writing about special effects, I regularly found myself banging a particular drum, and eventually had to stop myself getting repetitive. In my research on special effects, I continually found practitioners, and some critics espousing a belief that virtual actors were soon going to reach such a perfect state of simulation that spectators would be unable to tell them apart from the real thing. The following comes from a paper I wrote for Stacy Gillis’ collection The Matrix Trilogy: Cyberpunk Reloaded:

It would be all too easy to fall for the suggestion that the age of the synthespian is imminent, and that soon human actors will interact with computer-generated co-stars without the audience realising which is which. Will Anielewicz, a senior animator at effects house Industrial Light and Magic, promised recently that “Within five years, the best actor is going to be a digital actor”. The apotheosis of an animated character into an artificially intelligent, fully simulacrous figure indistinguishable from its carbon-based referent is technically impossible, at least in the foreseeable future, but visual effects are not definitive renderings of a character or event but indicators of the state-of-the-art offering “a hint of what is likely to come” (Kerlow) in the field of visual illusions in the future. It is understandable that such a competitive industry needs to maintain interest in the potential of its products, but the mythos of the virtual actor has infiltrated the Hollywood blockbuster in recent years […]

For the record, I regret the phrase “technically impossible”: I think the barriers to producing perfect synthespians are not primarily technical, but cultural and economic (if there was enough demand, money would have been found for even more research and development even sooner). I was using the “mythos” or concept of the virtual actor, the belief in inevitable progress, as an example of the kind of teleological argument that I wanted to unpick. It wasn’t hard to find it surfacing in other places. This from another essay in James Lyons and John Plunkett’s Multimedia Histories: From the Magic Lantern to the Internet:

Kelly Tyler, of NOVA Online, a science-based website, has identified the photorealistic human simulacrum as “a new digital grail.” Damion Neff, an artificial intelligence designer for Microsoft video games has called it “the Holy Grail of character animation.” In his keynote address at the 1997 Autonomous Agents Conference, Danny Ellis listed the emotionally intelligent virtual actor as one of four “holy grail” in the field. In May 2003 John Gaeta, discussing his visual effects work on The Matrix Reloaded in the Los Angeles Times, referred to a believable digital human as “the holy grail” of our world. It seems that the Grail analogy has found some currency, at least amongst those working in the relevant creative industries. This frequently uttered analogy sums up the suggestion that technologies of visual representation have been working inexorably towards a final goal, but they might also inadvertently hint that such a goal is essentially elusive.

The development of special effects over time suggests scientific progress as motion towards a logical conclusion, their development effected by a series of refinements and improvements to existing mechanisms. Certainly, computer-generated imagery, with its increasing photographic verisimilitude permitted by faster processing speeds and more efficient rendering software, appears to be advancing at a quantifiable rate, implying a final destination of absolute simulation, a point where a digital human being can be rendered to a level of detail indistinguishable from actual flesh and bone, and possessing enough (artificial) intelligence to be a star offscreen instead of just a hyperreal cartoon upon it.

So, how can this teleology by questioned? How do we construct a more continuist approach to historicising these spectacles in the face of such persuasive technological progress? By drawing the focus away from the dazzling verisimilitude of illusory technologies and focusing on the conceptual questions which underpin their fascinating surfaces. We can observe antecedents of the virtual actor and note that the same spectacular strategies, prompting the same ontological questions, were in play.

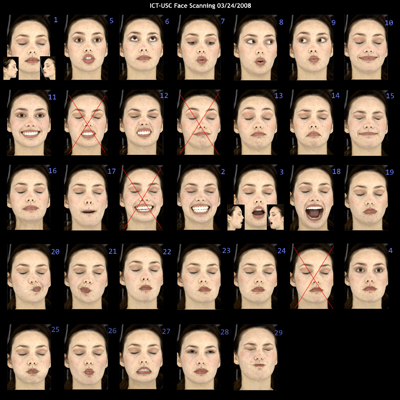

That’s enough self-promotional recapping. I hope you get the message that, whatever actual developments there might be in imaging technologies that can simulate properties of human figures, there is another narrative here. As Lev Manovich put it in The Language of New Media, “throughout the history of computer animation, the simulation of the human figure has served as a yardstick for measuring the progress of the whole field.” So, just to make sure you stay interested, every now and then some industry insider pipes up and tells you that you’re just months away from being fooled into believing in a bit of CGI as a living, breathing person. So, here we go again. Only this week, Image Metrics have announced that they’re very close to the Holy Grail. Take a look at this video of actress Emily O’Brien:

[Find out more about the process, or watch a higher resolution version of the video here.]

Pretty impressive stuff. As you can probably tell, her face has been digitally captured and mapped over her actual face, not because it’s a useful thing to do, but because it puts the digital and the flesh versions of Emily close enough that we can compare them. Presumably, the real benefits of the process will be seen in applications that can map her face onto her stunt double, or onto another actress if Emily, heaven forbid, suffers a terrible accident halfway through shooting a very expensive blockbuster movie. Or it might help our already beloved stars transcend the limits of their own bodies. Here’s the original post I spotted on IMDB:

1 January 2009 1:30 AM, PST

“Silicon Valley is on the verge of producing sophisticated software that will allow motion picture companies to create actors on a computer who are visually indistinguishable from real people, San Jose’s Mercury News reported today (Thursday). In the words of the newspaper, which closely follows the sofware industry, when software engineers finally achieve what it calls “the holy grail of animation,” stars would be able to “keep playing iconic roles even as they aged past the point of believability like Angelina Jolie as Lara Croft or Daniel Radcliffe as Harry Potter.” Rick Bergman, general manager of AMD’s graphics products group, told the Mercury News that his company “is getting real close” to producing computer-generated actors that will look identical to real human beings.”

Does anyone honestly believe that there is a call or a need for technologies for sustaining the shelf lives of these people? Of course not – it’s just a distracting excuse to avoid the real explanation, which is closer to “we’ve got this cool gadget, and we really want to show it off.” I remain skeptical about claims of impending perfection in virtual actors not because the technology isn’t impressive, but because the grand deterministic narrative of progress is overriding the reality of the situation. One savvy poster over at the Blu-Ray forum says it all in a manner that needs no elaboration from me:

Oh, dear lordy, they (meaning, JU) posted the article here, too…The same exact article (with different star insertions, hence the ’01 dated Tomb Raider ref) that studios plant once a year by the clock, in the hopes they can finally get that CGI resurrected dead-Karloff-and-Chaney Frankenstein vs. the Wolfman movie going again, because it sounded like such a neat idea back when Forrest Gump shook hands with JFK–

Twelve years, Final Fantasy, and Beowulf later, and they’re STILL trying to sell us on “With virtual actors, we could bring George Burns back from the dead, and he’d look so real!“

In case you needed more convincing, I dug up this old article from The Boston Globe, 23rd May 1999. There’s that grail again:

It sounds like a plot from a sci-fi pulp, or an old B movie: A snaggle-toothed scientist toils in the laboratory, perfecting his creation. A touch-up here, a tiny tuck there. But this is not some green-gilled monster from the house of Dr. Frankenstein; it’s a realistic human with shiny hair, glittering teeth, and liquid eyes. The pressure is on to beat other genetic geniuses racing to create human clones. Suddenly, there’s a burst of energy – and voila! – the model comes to life. Blink your eyes, and it’s Marilyn Monroe. Blink again, and it’s James Dean.

This scenario isn’t as far-fetched – or as far off – as it might once have seemed. In this case, the scientists in question are digital doctors: computer programmers developing the software needed to create a photorealistic digital actor, or ”synthespian.” Special-effects wizards have already created convincing digital dinosaurs and dolls, aliens and ants, stuntmen and superheroes. And the two biggest box office draws of the moment – The Mummy and a certain prequel that unfolds in a galaxy far, far away – showcase digital creatures.

So why not digital humans? Why not virtual stars?

”The digital actor has been the Holy Grail forever, since the dawn of 3-D computer animation,” says Brad Lewis, executive producer of visual effects and vice president of Pacific Data Images, the firm that gave life to insects in Antz. ”There’s always been someone trying to do a hand or a face or some aspect of a human being that looked real.”

Some say realistic digital humans will be on-screen within the next five years. These synthespians could be brand-new characters or reincarnations of old legends, long cold in the grave. One Hollywood producer, for instance, is planning a film that would resurrect martial-arts phenomenon Bruce Lee; another is reportedly working on a digital version of an aging screen star (rumored to be Marlon Brando), restoring his youth and making him a contender for a manly role. Another producer got permission to re-create the late George Burns in a film called The Best Man, and a California firm, Virtual Celebrity Productions, has obtained the rights to digitally reproduce a handful of stars, including Marlene Dietrich and W. C. Fields.

Hang on. Did I read that correctly? W.C. Fields? I can understand how Dietrich’s pictorial stillness might translate relatively easily to a digital avatar, but is there anyone less suited to a CGI resurrection by the pixel pixies than W.C. Fields?! Well, they gave it a go a few years back with the Gepetto software (nice puppet reference, there) for real-time 3D animation. I can’t say the results were ever going to replace the memory of the real thing, but that’s not really the point. These rumours and promises build anticipation, expectation, and a sense that something is at stake. The defiance of death, age and human inadequacies is just a cover story for the real business of special effects.

Hang on. Did I read that correctly? W.C. Fields? I can understand how Dietrich’s pictorial stillness might translate relatively easily to a digital avatar, but is there anyone less suited to a CGI resurrection by the pixel pixies than W.C. Fields?! Well, they gave it a go a few years back with the Gepetto software (nice puppet reference, there) for real-time 3D animation. I can’t say the results were ever going to replace the memory of the real thing, but that’s not really the point. These rumours and promises build anticipation, expectation, and a sense that something is at stake. The defiance of death, age and human inadequacies is just a cover story for the real business of special effects.

Look at the Curious Case of Benjamin Button. The stated aims of the film, in which Brad Pitt’s character ages “backwards”, might be to integrate visual effects so seamlessly that they don’t distract from the character-driven, Oscar-baiting emotional truth of it all, but there’s no getting away from the fact that, by centralising the concept of a spectacular body like Benjamin’s, a magnet for diegetic and extra-diegetic curiosity, the film can’t help but draw attention to the visual effects used to achieve the concept’s visualisation. Pitt’s body becomes a laboratory for all kinds of tricksy bits of CG animation and performance capture, and there’s a complex connection between the fascinated gaze that attaches to the character’s condition, and the one that fixes on the image of a movie star transformed into a recognisable but fundamentally changed series of physiques by means of cinematic tricks. When Benjamin strikes muscleman poses in the mirror, it’s as much about technological display as it is about his own narcissistic enjoyment. The discourses around the futuristic capabilities of digital imaging technologies shape expectations about how a particular special effect is to be viewed and appreciated. There’s an element of promotional hype in play, but by providing a set of measurable goals and projected rationales, the impression given is that special effects are contributing to a worthwhile cause with a pre-determined path, instead of offering random and occasional attractions; it all makes sure that you stay interested, and keep buying a ticket for the next attraction, and then the next. Special effects, like movie stars, exist intertextually – they provide reassuring continuities: we are expected to keep watching how they develop from film to film, how each is an improvement upon the last – so it makes sense that a certain weight of expectation should hand on the predicted hybrid of a special effects movie star, an all-digital, perhaps artificially intelligent character actor who passes for flesh and blood before your very eyes. But to truly deliver on that promise to deceive would defeat the object of the special effect, which was to attract and hold that multi-focus spectatorial gaze. What’s the use of a spectacular attraction if nobody notices it?

See also How Special Effects Work 1: The Sandman & How Special Effects Work 3: Now That’s Magic…

Lisa Bode, ‘“Grave Robbing” or “Career Comeback”? On the Digital Resurrection of Dead Screen Stars’, in History of Stardom Reconsidered. Edited by Hannu Salmi et al. (Turku: International Institute for Popular Culture, 2007) Available as an eBook at http://iipc.utu.fi/reconsidered/.

You probably don’t need me to tell you how fabulous

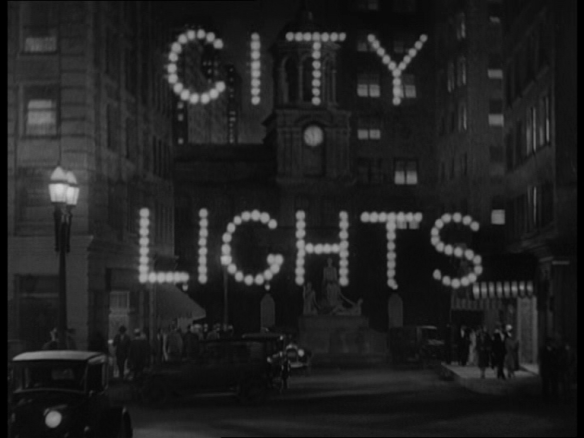

You probably don’t need me to tell you how fabulous  By 1931, when City Lights was ready for release, the rest of Hollywood had

By 1931, when City Lights was ready for release, the rest of Hollywood had

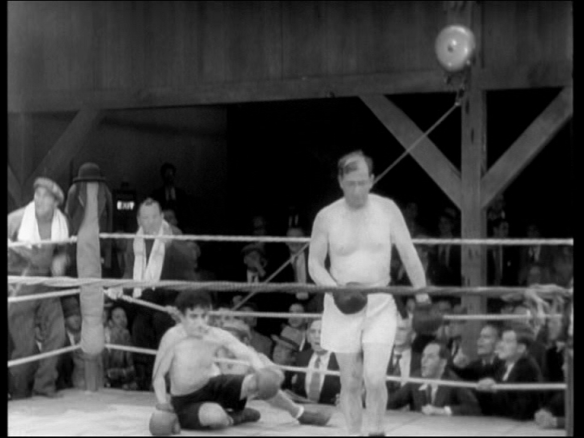

Other sounds are similarly troublesome. See for instance the lovely sequence where, drunk at a party, Chaplin swallows a whistle. A fit of hiccups makes him tweet involuntarily, dismaying a singer who is trying to perform, and attracting cabs and dogs when he rushes outside. It’s a beautifully worked joke, stretched just far enough to avoid becoming tiresome, and only partially reliant on the post-synched sound effect, which appropriately disrupts the musical soundtrack, stressing the sudden, stared-at embarrassment Charlie suffers. During the boxing scene, Charlie’s neck gets caught in the

Other sounds are similarly troublesome. See for instance the lovely sequence where, drunk at a party, Chaplin swallows a whistle. A fit of hiccups makes him tweet involuntarily, dismaying a singer who is trying to perform, and attracting cabs and dogs when he rushes outside. It’s a beautifully worked joke, stretched just far enough to avoid becoming tiresome, and only partially reliant on the post-synched sound effect, which appropriately disrupts the musical soundtrack, stressing the sudden, stared-at embarrassment Charlie suffers. During the boxing scene, Charlie’s neck gets caught in the

These recurrent, repetitive types of action add up to a mode of performance that sees Chaplin’s body in constant tension between composure and error. His body is challenged at every turn by threats to his dignity. It all begins from a logical starting point: he begins the film asleep on a statue, an unwelcome pest on an image of static decorum. For much of the rest of the film, he will struggle to stay still or posed against the tide of unpredictable movements that characterise his experience of the city.

These recurrent, repetitive types of action add up to a mode of performance that sees Chaplin’s body in constant tension between composure and error. His body is challenged at every turn by threats to his dignity. It all begins from a logical starting point: he begins the film asleep on a statue, an unwelcome pest on an image of static decorum. For much of the rest of the film, he will struggle to stay still or posed against the tide of unpredictable movements that characterise his experience of the city. Much of the comedy of Chaplin’s performance style derives from his attempts to maintain his dignity, as if to deny his derelict status. He tries to behave in a manner befitting his increasingly dishevelled suit (notice how the tipping of his hit becomes like a nervous tic), while all around him see through the disguise (e.g. the paper boys who taunt him, tearing fingers from his gloves or a patch from his trousers; the butler who repeatedly ejects him from the millionaire’s mansion). His careful, fussy comportment is messed up by a series of involuntary responses to things that startle, trip or baffle him, or which taste funny.

Much of the comedy of Chaplin’s performance style derives from his attempts to maintain his dignity, as if to deny his derelict status. He tries to behave in a manner befitting his increasingly dishevelled suit (notice how the tipping of his hit becomes like a nervous tic), while all around him see through the disguise (e.g. the paper boys who taunt him, tearing fingers from his gloves or a patch from his trousers; the butler who repeatedly ejects him from the millionaire’s mansion). His careful, fussy comportment is messed up by a series of involuntary responses to things that startle, trip or baffle him, or which taste funny.

This may be why Chaplin loves to play

This may be why Chaplin loves to play

Also see the holdings of the

Also see the holdings of the

A news story caught my ear this morning: you know how it is when you’re waking up, making breakfast and reading a newspaper with the TV on at the same time? Well, since I didn’t catch the details of the story, I went online to find confirmation that divers have

A news story caught my ear this morning: you know how it is when you’re waking up, making breakfast and reading a newspaper with the TV on at the same time? Well, since I didn’t catch the details of the story, I went online to find confirmation that divers have

The question over the contents of the ship’s hold is a crucial one. If it was carrying ammunition, i.e. contraband, it would have become a “legitimate” target for German

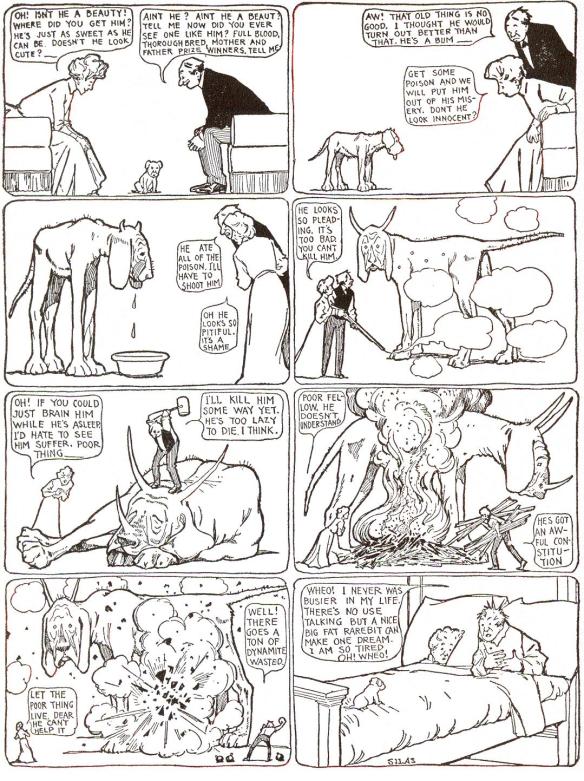

The question over the contents of the ship’s hold is a crucial one. If it was carrying ammunition, i.e. contraband, it would have become a “legitimate” target for German  Notice how the dog retains a believable musculature even as it reaches impossible proportions. It defies all spatial logic, straining at the corners of the frame, but McCay endows the dog with a convincing sense of weight and presence. This enhances the comic disparity between the enormity of the hallucination and the cute insignificance of the actual pup in the final panel, and is a good indicator of McCay’s interest in commenting on reality by not abandoning its physical precepts entirely.

Notice how the dog retains a believable musculature even as it reaches impossible proportions. It defies all spatial logic, straining at the corners of the frame, but McCay endows the dog with a convincing sense of weight and presence. This enhances the comic disparity between the enormity of the hallucination and the cute insignificance of the actual pup in the final panel, and is a good indicator of McCay’s interest in commenting on reality by not abandoning its physical precepts entirely.

Here are some other images that maintain that same diagonal framing of the sinking ship to stress its huge size and give it a horribly vertiginous angle as it keels over in the water. This propaganda poster is especially striking and self-explanatory:

Here are some other images that maintain that same diagonal framing of the sinking ship to stress its huge size and give it a horribly vertiginous angle as it keels over in the water. This propaganda poster is especially striking and self-explanatory:

Unfortunately, this also meant that the film was not ready for release until 20th July 1918, months before the end of the First World War, and too late to play a role in instigating retaliation. But it remains an extraordinary piece of propaganda. The final image is of a woman clutching a baby, sinking below the waves, fading into the abstract play of bubbles onscreen: the film’s simplest drawing may be its most powerful. This shot is drawn from Fred Spears’ famous “Enlist” propaganda poster of 1915-16:

Unfortunately, this also meant that the film was not ready for release until 20th July 1918, months before the end of the First World War, and too late to play a role in instigating retaliation. But it remains an extraordinary piece of propaganda. The final image is of a woman clutching a baby, sinking below the waves, fading into the abstract play of bubbles onscreen: the film’s simplest drawing may be its most powerful. This shot is drawn from Fred Spears’ famous “Enlist” propaganda poster of 1915-16: