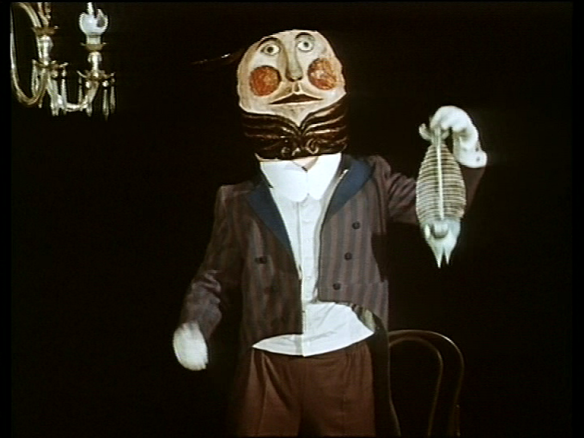

Two magicians take the stage, seated side by side against an all-black backdrop. Each insists with a raised hat and a hand gesture that the other should perform first. Each wags a finger in refusal. The exchange has all the signs and mimes of polite cordiality, but the stiff movements suggest that these are insincere formalities. Finally, one of them, Mr Edgar, agrees to perform his first trick. Removing his hat, he reaches into it and pulls out a large fish.

Raising a lid on his own skull, Mr Edgar tosses the fish inside and turns a crank in his ear, until the bare skeleton of the fish can be plucked out again, having been digested by the gears and cogs inside the magician’s cranium. He rubs his tummy to indicate a good meal has been had, though his face betrays no signals of enjoyment. In Svankmajer’s films, eating is a symbolic ritual whereby bodies process other symbols and exhaust them. Mr Edgar’s rival, Mr Schwarzwald, applauds the trick and steps up to perform his own. He strings up a tightrope between two chairs and takes a violin from out of his hollow head. Mr Edgar fills his ears with cotton wool to guard against the music. To the violin’s tune, an assemblage of objects leaps from Mr Schwarzwald’s hat and forms into a dancing horse.

For his next trick, Mr Edgar pulls two violins out of his head and, sprouting extra arms, transforms himself into a one-man-band of drums, brass and woodwind.

Mr Schwarzwald is keen to congratulate his fellow performer, but the handshake he delivers is ferocious in its finger-crushing force. He continues the theme of self-replication by juggling with multiples of his own head, and then it is Mr Edgar’s turn to administer an exhausting handshake to show his admiration for this magical feat.

His third trick sees him training the chairs to dance, tumble and jump through a hoop. Once this is concluded, Mr Edgar evades Mr Schwarzwald’s handshake for as long as possible, but finally he is caught, and the gesture of congratulation is powerful enough to tear his arm from its torso. Mr Edgar responds by punching his rival’s head off. The fight continues with a flurry of dismembering violence until only the two arms remain, locked together in a grim handshake. Communication has broken down until the hands are revealed as the drivers of this interplay – the heads have been shown to be empty of brains and agency – they are mere recepticles for the apparatus of spectacle, while the hands are the indexes of meaning and attitude with their gestural language.

As I embark upon a period of research into the work of Czech surrealist Jan Švankmajer (as part of a larger project on puppetry and cinema), this short film is my starting point, and it reveals to me the challenges that lie ahead. Often we have to look carefully at films to come to terms with their idiosyncrasies, but Švankmajer’s work is particularly daunting in its concentration of allegory and allusion. I’m hoping that my research will be able to supplement my initial response to the film with a broader frame of critical, historical and political reference, but these are my first thoughts on The Last Trick, his first film as director. For eleven minutes, two magicians do battle, and their tricks require a montage of colliding images and a range of animation techniques: the two actors wear giant masks on their heads, probably papier-mâché, making them look like living, stringless marionettes, and Švankmajer manipulates them accordingly. He persistently blurs states of being by using these half-puppets that unsettle us by refusing to act as either one thing or another. The black backdrop allows a bunraku performance of sorts, with objects appearing to fly and float unaided through space; frame-by-frame animation moves the eyes of the masks; a shot of pixilation makes their bodies flit around the stage in a lightning fast chase. These are endlessly mutable bodies, but there is none of the joyous spectacle of Melies’ filmed tricks here – the artifice is always signposted, never seamlessly suggestive, and the stolid expressions on the masked faces convey no fun, only procedure and routine.

Combative communication and variegated violence will recur in Dimensions of Dialogue and Virile Games amongst others (I’ll blog about these at a later date, I hope), piling up a snowballing rush of physical destruction. A number of the short films construct these repetitive, mechanical situations that continue until the mechanism breaks down, as if the film itself is wearing out its own structural circuit. While the puppethood of the characters in The Last Trick blocks the verisimilitude of the violence, it urges allegorical readings: puppets are what we use to stand in for or embody a particular theme, ideology or emotion when a human performer might pollute it with specifity and invidiuality. The “story” element of duelling magicians jealously escalating their competitive spectacles might be a premonitory tale of art spoiled by human partiality or commercial pressures (the winner will be he who compromises himself the most, sacrificing his body and soul for the audience’s delectation), or it might be a snapshot of how the most ferociously fought battles are internecine struggles rather than those between competing ideologies, a drama about the impossibility of compromise, of selfless dialogue. In any case, Švankmajer invests his objects with a powerful thingness: extreme close-ups serve not to reveal emotion or intent, as they might do with human actors, but the physical textures of the objects on display. I want to know why this is the case. What are the specific ways in which objects and specificially puppets, which are both performers and objects, function in Švankmajer’s films? I have a feeling that a detailed answer to this question might help me to model an analytical framework for puppetry more generally across many and varied film texts. Hopefully, I’ll be able to pool some of my notes and findings here as I go along.

Additional Observations:

I should note that, for all my Švankmajeric needs, I’m working from the British Film Institute‘s fabulous DVD collection, Jan Švankmajer: The Complete Short Films. Hats off to the BFI: they’ve really raised their game in the past few years and fully embraced the potential of DVD. This 3-disc set compiles all of the director’s short films (the clue is in the title) and wraps them up with three hours of extra stuff, including “a bonus short, Johanes Doktor Faust (1958); the original 54-minute version of The Cabinet of Jan Svankmajer (1984) with a brand new introduction by the Quay Brothers; the French documentary Les Chimres des Svankmajer (2001); interviews with Jan and Eva Svankmajer and examples of their work in other media. There’s also a chance to see some Svankmajer special effects, created for commercial Czech features when he was banned from making his own films. The 54-page booklet includes an introduction to Svankmajer by Michael O’Pray; detailed film notes by Michael Brooke, Simon Field, Michael O’Pray, Julian Petley, A.L. Rees and Philip Strick; notes on the extras and much more.”

I should note that, for all my Švankmajeric needs, I’m working from the British Film Institute‘s fabulous DVD collection, Jan Švankmajer: The Complete Short Films. Hats off to the BFI: they’ve really raised their game in the past few years and fully embraced the potential of DVD. This 3-disc set compiles all of the director’s short films (the clue is in the title) and wraps them up with three hours of extra stuff, including “a bonus short, Johanes Doktor Faust (1958); the original 54-minute version of The Cabinet of Jan Svankmajer (1984) with a brand new introduction by the Quay Brothers; the French documentary Les Chimres des Svankmajer (2001); interviews with Jan and Eva Svankmajer and examples of their work in other media. There’s also a chance to see some Svankmajer special effects, created for commercial Czech features when he was banned from making his own films. The 54-page booklet includes an introduction to Svankmajer by Michael O’Pray; detailed film notes by Michael Brooke, Simon Field, Michael O’Pray, Julian Petley, A.L. Rees and Philip Strick; notes on the extras and much more.”- Although he’s not primarily concerned with a continuity style in this or most of his other films, note that Švankmajer uses the chandelier to lodge the film in a coherent space. It is there in many shots, and although its exact position changes, it is either in the left or the right of the frame to indicate which magician is performing, formalising the adversarial divide between them, and finally in the middle in that shot of the final handshake: at this point it stresses the symmetrical detente of the reluctant, stalemated truce.

- What are we to make of the beetle that crawls through the film, oblivious to the increasingly pugilistic contest until it is shown dead in the final shot? It can be seen on the magicians’ faces and inside their skulls like a nagging idea, but is apparently a casualty of the limb-tearing showdown. Insects are nature’s automata, machinic little things with rigid bodies and seemingly clockwork gait. But next to the hard-headed puppet conjurors on show in this film, the beetle is the most vivid, enlivened thing on display. Paul Wells calls it “the catalyst by which the interface between man and machine fails”, adding that it serves as “a narrational provocateur by which Svankmajer could reveal the rebellion in the construction of the contemporary body”. I don’t think I can say it any better than that.

- More from Paul Wells, whose article “Body Consciousness in the Films of Jan Svankmajer” (which you can find in Jayne Pilling’s A Reader in Animation Studies) is a typically lucid summary of how the director uses animation to articulate his sociopolitical theses about the place of the body in constituting the human subject in society: “Svankmajer uses the ritual of performance to suggest a model of difference only to imply that humankind will always fall prey to its own inability to properly reconcile the repeated failings and flaws of its evolutionary sensibility. The two magicians in The Last Trick are metaphors for Svankmajer’s social vision as it is played out through the contradiction inherent in the body as it is simultaneously liberated though art but mechanised by socio-cultural practice. Svankmajer’s quasi-surrealist approach represents the magician as a mechanism which possesses the inherent possibility of failing.”

Pingback: Punch and Judy (Jan Švankmajer, 1966) « Spectacular Attractions

Pingback: Jabberwocky (Jan Švankmajer, 1971) « Spectacular Attractions

Pingback: Flora (Jan Švankmajer, 1989) « Spectacular Attractions

Pingback: The Short Films of Jan Švankmajer « Spectacular Attractions

Pingback: The Last Trick (1964) « Stubenhockerei

With havin so much written content do you ever run into any problems of plagorism or copyright

infringement? My website has a lot of unique content I’ve either written myself or outsourced but it seems a lot of it is popping it up all over the internet without my agreement. Do you know any solutions to help prevent content from being ripped off? I’d truly appreciate it.

Hi, Laura. I haven’t had that problem, or at least I haven’t noticed it. Maybe I should do a speculative google to see if my work is being “borrowed”…