In the second of a trio of videos about Stanley Kubrick’s film, this week’s podcast is an audio-visual race through Marvel Comics’ adaptation of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Continue reading

In the second of a trio of videos about Stanley Kubrick’s film, this week’s podcast is an audio-visual race through Marvel Comics’ adaptation of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Continue reading

[Please note. This article contains quite a few spoilers. You can now download a version of this post as a podcast here.]

With Watchmen loitering, smell-like, in cinemas, it seems like a good time to revisit another film that aimed to deconstruct the ethics and boundaries of superheroism. It might have seemed like Moore and Gibbons’ original comic books (published 1986-7) would have been the final word on superheros and their social worth (reaching the conclusion that you’d have to be mentally unstable to want to dress up in spandex to fight crime, and that their brand of tooled-up vigilantism is ultimately more destructive than salvatory), but it seems that it is now difficult to do a superhero film without problematising issues of heroism and direct action; if they continue on their current course, for instance, the Batman films might be swamped by their own agonising about appropriate responses to villainy, crushed by indecision. Pixar’s The Incredibles is a family-friendly version of Watchmen in which outlawed superheroes are forced to adjust to the mundanity of regular lives, and G. Xavier Robillard’s comic novel Captain Freedom: A Superhero’s Quest for Truth, Justice, and the Celebrity he so Richly Deserves, sees its hero’s crimefighting services bureaucratised and outsourced to Bangalore, while last year’s Hancock had messiah-for-hire Will Smith’s character struggling with the existential weight of his super status by drinking too much and washing too little. If the mythos of the superhero, playing out themes of justice and international conflict in colourful, diagrammatic forms, is still hugely popular, audiences seem less prepared to swallow it whole, without the digestive assistance of irony and self-awareness. Or, it might just be that the discursive, speculative nature of super-fictions, always testing the limits and dilemmas of vigilantism, is being brought to the fore.

I would hate for M. Night Shyamalan’s Unbreakable to get overlooked in this flurry of postmodern genre-fidgeting. Here was a director who gained so much attention for his third feature, The Sixth Sense, that it set up a huge dam of anticipation for his subsequent projects. This momentum has gradually drained away with a series of increasingly indulgent flops, the most disastrous being The Happening, which hit new lows of critical contempt. Connecting all of his films is a wish to update and explore genre cinema’s trashiest corners, always driven by an intriguing idea, even when the execution is duff. The Sixth Sense is a ghost story about mourning; Signs is an alien invasion B-movie told from the point of view most of us would actually have on such a disaster (cowering in the basement glued to CNN); The Village is an occult horror film with a twist that is either unfeasibly daft, or an incisive summation of America’s isolationist paranoia; Lady in the Water is impossible to recall without involuntarily shaking my head, but it thinks it’s an urban update of fairy-tales, but is actually a wonderless, jargon-laden dog; The Happening is Shyamalan’s 9-11 movie, and while I like the paradoxical idea of an invisible disaster seen only in the strange behaviour it prompts in its victims, it’s all very dull, enfuriatingly performed, and might be a thinly veiled push for intelligent design. Don’t let this tragic frittering away of talent taint your judgement of Unbreakable, his mature masterpiece that strikes a balance between a populist star vehicle and an uncompromising personal approach, where his rather prissy care over composition finds its affective match in the subject matter.

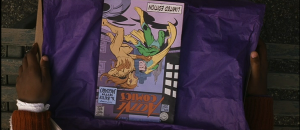

Unbreakable is the story of David Dunn (Bruce Willis, in an extremely contained performance, drained of all wisecrack), a football stadium security guard who is the only survivor of a train crash; he meets Elijah Price (Samuel L. Jackson: it’s to both actors credit that I’d completely forgotten their earlier pairing in Die Hard with a Vengeance), a comic book dealer suffering from brittle bone disease, who tries to convince Dunn that his unscathed escape from the crash reveals a superheroic secret identity. Gradually, Dunn is persuaded by portents that he possesses superhuman strength and a psychic ability to locate crime and its perpetrators. Finally, and you should skip to the next paragraph immediately if you don’t want to know the ending, Elijah reveals that he is Dunn’s opposite, his supervillain nemesis-in-waiting: it was he who caused the crash, and a number of other “accidents”, in his search for his invulnerable opposite number.

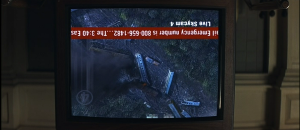

Judging by the notes accompanying the DVD edition, Shyamalan seems to think that making Unbreakable was a simple case of taking seriously an oft-derived medium (hence the opening titles citing statistics to show the prevalence of comic-book readership in the USA) by giving it the realistic treatment it is usually denied:

All of the scenes are being done in one shot instead of using traditional coverage, so that the movie is much more realistic for the viewer … as if they were right there watching something that is actually taking place in real life and not on a movie screen.

If the director thinks that the use of long takes serves only to confer a sense of Bazinian realism to the film, he’s selling himself short. The tactic is immediately distinctive (the average shot length is around 23 seconds, at a time when the average was 4.7 seconds), but it does more than give the viewer a window on the scene – the perspective is carefully chosen in every case.

Bruce Willis is introduced in a three-and-a-half-minute tracking shot in the train. It’s a tremendously low-key preamble to a massive disaster. Willis tries to pick up the passenger next to him (he surreptitiously removes his wedding ring), and the conversation is captured with a track that shuttles between their faces through a gap in the seat; they are never shown in the same shot. It might be the POV of the child in the next seat, and it might be a gimmick, but the smooth, sinister sidling of the camera succinctly captures the hesitant sneakiness of the exchange.

Following the crash, Dunn wakes up in the hospital where a doctor explains that there are only two survivors. The other passenger is in the immediate foreground. As Dunn looks on, a red patch of blood appears as the patient expires, leaving him as the sole survivor, struggling with the guilt of his privileged otherness (a deleted scene was to have shown him being cold-shouldered by a priest he has approached for counsel). It’s an extremely overdetermined shot, in which Dunn’s alien status is consolidated by the needless death of another, all contained within the same shot to emphasise the growing sense of his strangeness, mirrored in the spread of blood, as if the foreground wound illustrates his own lack of injury. Shyamalan enjoys upsetting the usual hierarchies of cinematic space with the main information being delivered in the background while a separate drama unfolds in front.

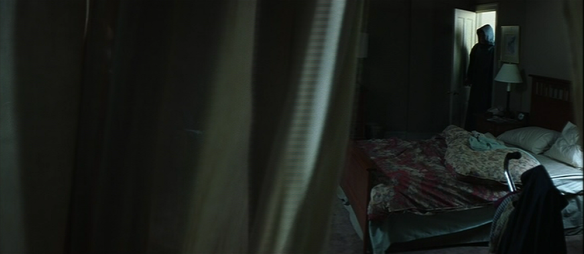

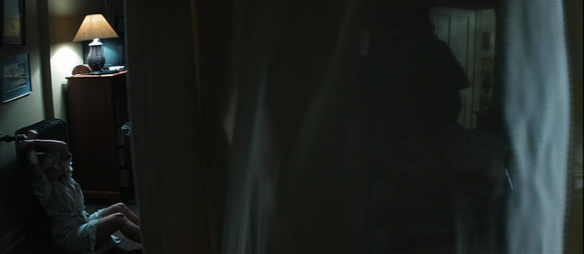

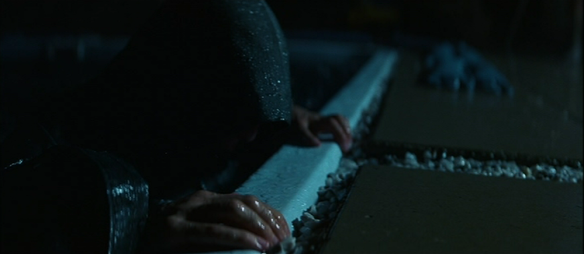

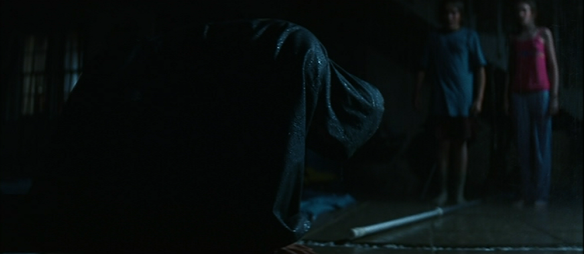

Another extraordinary composition during the climactic rescue scene is taken from behind billowing drapes which reveal enough of the room to show Dunn entering it, then another gap in the sheets reveals the woman tied up on the opposite side of the frame:

Several shots are taken upside down, partly to show the viewpoint of characters who are themselves upside down, but also to introduce a theme of perspective – his central characters are men who need to adjust their outlook in order to see the codes of predestination working around them.

Shyamalan likes to build his films around patterns and portents: this is how he weighs them down with a sense of fate, an organised universe into which audiences are invited to step, usually just ahead of the characters, who take a little longer to notice what’s going on: primed to expect the fantastic, viewers are far more ready to accept the implausible explanations that the fiction’s inhabitants deny. This isn’t a film that asks you to wait for a shock ending to rewrite the prior events (as with The Sixth Sense), but one which lets you watch Willis’ character arrive at the realisation that has been signposted from the start.

Perhaps the most effective aspect of the film’s form is the way Shyamalan conveys Dunn’s alienation, his separateness, which initially seems like a moody, jaded emotional remove from the people around him, but comes to be a highly economical expression of the superhero’s dilemma, being a protector of society who must secret himself to conceal his essential difference. This is achieved in a series of compositions that distance him from crowds and segregate his sensory information (and, more obviously, by making his character a security guard on the periphery of the circuit of heroic football players in the game he can no longer play).

Often, conversations are conducted from indirect eyelines, or with only one speaker visible in the frame, further accentuating the gulfs between people. A crucial meeting with one of Dunn’s former teachers is conducted almost entirely in an over-the-shoulder shot that never delivers the reverse shot that would allow us to read her face. Some of the long takes might seem wilfully obscure or tricksy, using off-centre framings and unmotivated lateral tracks, but this slightly withdrawn approach always has a motive: if this is a film about a man coming to realise his “place in the world”, to become attuned with the purpose and patterns around him, it is expressed by having him get in synch with the movements of the camera; early in the film, the camera will drift away from him or keep him out of focus in a two-shot, but by the end it is tracking his movements, formalising his attainment of self-awareness. At moments of realisation, the camera strikes up a sympathetic correlation with his movements. See for instance, the weightlifting scene where he tests the limits of his newfound strength, and the camera rises and falls with his lifts, as if flexing along with his muscles, or the beautiful moment where he emerges from the swimming pool, overcoming his aquatic weakness, and the camera reframes, willing him on as he drags himself out of the water.

It’s lucky Shyamalan made this before The Happening, before Lady in the Water. It’s a sombre, mournful affair that would be a hard sell if execs hadn’t been softened up by The Sixth Sense. It doesn’t renege on its aesthetic pledges by descending into spandex and flying: there’s only one action scene, and it’s a halting, desperate event. Plus, Unbreakable allows skeptical viewers to interpret all of its miracles as pure coincidence, a seductive illusion crafted out of suggestive compositions. It shows you so many patterns, so much structure, that you want to believe that the world is this way, and that the extraordinary is in there somewhere, if only you can find the right angle from which to look at it.

Read more: